Home » Posts tagged 'green zone'

Tag Archives: green zone

Zero Dark Thirty

Zero Dark Thirty (Kathryn Bigelow, 2012) joins a curious set of films that includes Apollo 13 (Ron Howard, 1995), Titanic (James Cameron, 1997) and United 93 (Paul Greengrass, 2006), among others. You know what is going to happen, so the filmmaker has to generate tension and suspense despite this. Kathryn Bigelow delivers this with remarkable power in her film about the hunt for Osama Bin Laden, or UBL as the CIA referred to him. Focused on the CIA analyst leading the hunt, Maya (Jessica Chastain), Zero Dark Thirty is compelling, gripping, thrilling and disturbing, striking the viewer in the head, heart and guts.

Zero Dark Thirty effectively begins where Paul Greengrass’ film United 93 ended. The opening “scene” of ZDT sets the tone, as a black screen fills the frame with only the ominous date, September 11, 2001, visible. Recorded messages pepper the soundtrack, (presumably) the actual recordings of calls made to relatives aboard flight United 93, and 911 calls made from within the World Trade Center. Although, like the rest of the world, I watched the destruction of the Twin Towers with mounting horror, voices of the doomed was not something I had heard before. Particularly chilling and moving were the desperate pleas of a woman describing the blazing floor beneath her, and the 911 operator trying to offer comfort, before the woman is cut off and the operator can only say “Hello? Hello? Oh my God…”

The presence of such “real-life” footage places the viewer in the midst of events, a conceit that continues throughout the film and is achieved both narratively and stylistically. The following scene drops us into the middle of an interrogation scene, with terror suspect Ammar (Reda Kateb) beaten by hooded figures while Dan (Jason Clarke), a CIA operative, questions him. This scene introduces our protagonist, Maya, fresh arrived from Washington. The cinematography is intimate, the editing abrupt, cutting from close-ups of one face to another, as the frame wavers slightly. The soundtrack is charged with menace, both from the sounds of the suspect being pummelled and Dan’s threats: “You lie to me, I hurt you”. This approach permeates this film, Bigelow’s camera often placing the viewer at an uncomfortable proximity to the action onscreen.

Nor is this action necessarily violent – even during briefings with Maya’s team, the camera sits like an extra attendee, almost but not quite at the invasive level. Never is there a look direct to camera, which adds to the sense of intrusion – we are there, somehow involved but not a part of the story, looking on from a position that is uncomfortable because of its uncertainty. The tension generated by this uncertainty is increased by intercutting the fictionalised story of Maya and her team with dramatisations of actual events, highlighted by super-text that informs the viewer of the date and time. This foreshadows what will happen, such as when a bus appears and the caption declares that this is London, July 7 2005, and the viewer knows what is coming. This attack, as well as the bombing of the Islamabad Marriot Hotel and a US base in Afghanistan, still delivers a shock when the explosion comes, not because it is unexpected, but because it is so utterly incongruous. A bus driving through London is not supposed to blow up; people sitting in a hotel restaurant are not meant to be flung to the floor by an explosion. ZDT communicates to a very sheltered person (me) an approximation of the shock and horror of terrorist attacks, and while I may know intellectually what is coming, the visceral impact is still something I am unprepared for.

The film’s suturing of “actual” and fictional events anchors the viewer further within the events of the narrative. Just as Maya is discomfited by the torture of Ammar, so are we (more on the torture later). Just as she receives a confusing plethora of information, so are we confronted with a bewildering range of locations, characters and events. Super-text informs us of the scenario, but it often reads “CIA Black Site” at “Undisclosed Location”, presenting a fragmentary look into a covert world. This seems obvious – ZDT is a film about secret agents doing secret things – but Bigelow’s presentation allows us to vicariously experience Maya’s investigation, scenes pieced together with little central propulsion, just as the hunt for UBL is pieced together through scraps and snatches of information. Profoundly postmodern, the film is the search for a master narrative, an attempt to regain an understanding that was shattered by the events of 9/11.

The dialogue is peppered with jargon, a feature of the genre. Spy film dialogue is similar to that of hard-boiled noir, as it conveys both the environment and the people shaped within it, but it varies depending on the type of espionage being depicted. The jargon of ZDT, much like that of the Bourne franchise, is very different from the rather charming public school banter of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy or even the office chat of the Jack Ryan franchise. Terse, cold and impersonal, even in moments of high emotion, spy jargon expresses the post-human sensibility of contemporary espionage. Not only is intelligence the gathering and assembly of information, but the people involved become cyphers as well. It is perhaps not surprising that torture would emerge within this environment, empathy and humanity placed to one side as human beings become simple receptacles of information. This dehumanisation is one of the more chilling aspects of the film.

Critics such as Slazoj Zizek and Naomi Wolf have accused ZDT of endorsing torture, with Wolf going so far as to liken Bigelow to Leni Riefensthal. There are several problems with this view, which is an imposed reading rather than a careful analysis. Torture is depicted, including the beating of suspects, waterboarding and threats to turn Arab suspects over to Israel (who are, presumably, even more brutal). But it is easy to overstate the representation of torture rather than consider it in context. Firstly, the torture occupies only a small portion of the film. Whereas 24 has multiple scenes of torture-as-spectacle, seemingly as integral to the drama as gunfights and explosions, and Rendition (Gavin Hook, 2007) presents prolonged scenes of torture specifically to criticise the practice, ZDT depicts one victim, in the first act, with scenes that feature him being water-boarded and shut in a box. Secondly, torture of suspects is one of a variety of methods used within the context of an investigation. Surveillance of suspects, monitoring of financial transactions and commercial travel, monitoring of phone calls and e-mails, paid and bribed sources, reviewing and re-evaluating existing intelligence – all of these feed into the investigation. Crucially, the piece of information extracted from a tortured suspect is found to already be in the CIA’s possession, making the torture redundant. The fortified house in Pakistan that turns out to be the hideout of Bin Laden is discovered by following a different suspect, further demonstrating the futility of torture. Wolf and Zizek might see this as reason that ZDT “should” launch into a criticism of the torture programme, and the fact that it does not is grounds to condemn the film.

I have a big problem with imposed readings, the suggestion that a film (or any text) “should” do what reader X decides is right. Rather than declaring that the text is only morally permissible if it takes the stance that reader X dictates, why not look hard at what the text actually does and says? Zizek dismisses this sort of response with the declaration that torture is simply wrong, and no debate about it is necessary. He has a point – I agree that torture has no place in a civilised society – but his evidence for Zero Dark Thirty’s endorsement of torture is dubious. ZDT presents torture as part of CIA procedure, which Zizek calls “normalisation”, perhaps to echo the “banality of evil” used in reference to the mathematical precision of the Holocaust. When President Obama appears on the television stating that the United States does not engage in torture, the CIA agents barely react. This may lend credence to Zizek’s argument: the film offers little reaction to the torture and therefore makes it normal. Zizek argues that ZDT is far more immoral than 24 because of its failure to present torture as horrific, making it part of business as usual: “The normalisation of torture in Zero Dark Thirty is a sign of the moral vacuum we are gradually approaching”, says Zizek. I suggest, however, that business as usual in ZDT is itself disturbing.

As mentioned above, Zero Dark Thirty is concerned with the search for a grand narrative, the world shattered into post-human cyphers of information. These cyphers express the only reaction to the torture: Maya grimaces and looks away from the suffering victim; Dan returns to the US because he has seen enough. This raises accusations that the discomfort of white Americans is of greater significance than the actual suffering of Middle Eastern Muslims. There is an established argument that Hollywood always privileges white Americans over any other demographic, ignoring the suffering of (in this case) Middle Eastern Muslims who are being physically and psychologically harmed. I consider myself a liberal, critical of the military-industrial complex, but am dubious of Hollywood being an uncritical promoter of this complex. I am dubious because accusations like those of Zizek and Wolf overstate the case to a self-righteous and patronising degree, stating their imposed readings as self-evident truths of some undefined utopian ideology. The subject of Zero Dark Thirty is the CIA hunt for UBL, and the people involved in this hunt. I see nothing wrong with this dramatic, compelling and relevant subject, and the way that the subject is handled in the film presents a grim and unsettling picture. It is not an outright condemnation like Rendition or Green Zone (Greengrass, 2010), but it is very arrogant to criticise filmmakers for not doing something they never set out to do.

Furthermore, Zero Dark Thirty does not endorse torture because the practice proves to be redundant in the course of the investigation. Nor is the investigation itself presented in a positive light, because at no point is there any sense of triumph. Maya has her victories, such as when her station chief Joseph Bradley (Kyle Chandler) grants her further resources, and she and her colleague Jessica (Jennifer Ehle) make breakthroughs. The final assault on Bin Laden’s compound is not presented as a gung-ho mission, with Special Ops guys back-slapping and high-fiving, but with all the seriousness that befits an incursion into enemy territory when the stakes are very high. When the team penetrate the house, Bigelow maintains the uncomfortable intimacy that has run throughout the film, which escalates into an incredibly tense set piece. Viewed largely through the team’s night-vision goggles, the compound takes on an unworldly, threatening quality, vision restricted by closed doors, staircase curves and bends in corridors. Violence occurs in quick bursts of gun fire, shocking in its suddenness with a sound design that emphasises its immediacy. Tension and fear permeates the sequence, a microcosm of the film as a whole. The viewer is placed in close proximity to the events onscreen, allowing us to feel the threat and danger posed to the soldiers. Nor are these soldiers presented as heroes – the film presents them as highly-trained, highly-equipped professional killers. Terse commands, again in military jargon, are the order of the day, rather than bravado and machismo. Once again, we see a dangerous world of post-human cyphers, operating on the basis of disembodied instructions through modern technology.

The eventual identification of the corpse of UBL is not accompanied by whoops of delight or shouts of triumph. At best, there is relief, relief that something has been accomplished in this on-going struggle. But what has truly been achieved? Considering the events of the film in context, a viewer would be aware that the death of Bin Laden has not ended the War on Terror, so the result of this investigation is little more than a dead body in a bag (although some potentially useful intelligence is gathered as well).

Interestingly, we never see the corpse directly, only digital images of it, perhaps alluding to the controversy over whether the assassination ever actually took place. Maya provides the identification, but is she reliable? Clearly she has become obsessed, her commitment to locate her target consuming her completely while her colleagues are re-assigned or killed. Her identification is all we have to go on, and the final shot of the film lingers on her face, as she breaks down and softly starts to weep. Perhaps it is just relief, Maya allowing herself to feel the stress and let out the tension she has been holding for a decade. Could it be anger at herself for not getting the job done sooner? Or could it even be guilt at a deception she has perpetrated, because she was 100% certain Bin Laden was there, and the prospect of it not being him was just too much?

I am not a conspiracy theorist, so I think that the film does end with Bin Laden’s death and I interpret Maya’s tears as a release, as well as a device that neuters any sense of triumph. But the ambiguity of the film’s conclusion maintains its refusal to moralise, portraying events rather than judging them. We are aligned with Maya and her colleagues throughout the film, whether sitting uncomfortably close during meetings or looking over the shoulder of the attack team. The grand narrative that the hunt for Osama Bin Laden was supposed to recapture after 9/11 is not achieved, this is just one chapter in a post-human world of fragmentary data. Even the confirmation of Bin Laden’s death is only shown through digital images, themselves a disassembly of objects into data. This is another reason Zero Dark Thirty is no more an endorsement of torture than it is a criticism. It is not an apology for torture, nor a valorisation of the hunt for Osama Bin Laden, and neither a criticism nor endorsement of the CIA. It is a tale of absolute commitment to an ultimately pointless endeavour, that achieves nothing more than a release. This is what makes the film disturbing: the business as usual that Zero Dark Thirty presents is a world bereft of grand narratives and meaningful events, a world in which what we do matters little, and what we achieve brings us neither success nor peace.

“Argo” – balancing act extraordinaire

Argo accomplishes the remarkable feat of striking a balance between drama, thrills, laughs and politics. It could have been an outright comedy, sending up Hollywood in a merciless satire, and it could have been a thoroughly tense and gripping espionage thriller. To be both of these and more is testament to the craftsmanship of Chris Terrio’s screenplay and Ben Affleck’s superb direction, which handles the different styles necessary for the contrasting sections and maintains an appropriate tone across the disparate elements. Equally, Argo avoids the pitfalls of being either a tedious and offensive piece of anti-Iranian propaganda, or a ponderous piece of finger-wagging at the US.

Politics

Where The Iron Lady spectacularly failed to be political, Argo accomplishes a remarkable piece of political balance. In the current climate, propaganda and political correctness are in constant tension, and Argo manages this tension by not offering judgement. Affleck does not apportion blame for the hostage crisis, but also does not shy away from historical evidence. The opening storyboards that relate the history of Iran feature a nationalised oil industry that made the people prosperous, and the replacement of that government, with foreign aid, by one that would serve the oil interests of the USA and the UK. Consequently, the Iranian Revolution in 1979 seems a reasonable response to almost thirty years of foreign-backed government that disrespected traditional Islamic beliefs. Politically, this is a bold stance for Affleck to take, presenting an Islamic uprising as a political revolution rather than religious fanaticism. Terrorism does not come up, and while the Iranian Revolutionary Army is certainly intimidating and aggressive, the members are not presented as psychotic, but justifiably angry and indignant.

Nor does the film perform a laboured critique of US foreign policy. Plenty of films do this and many quite well, such as Rendition (Gavin Hood, 2007), Fair Game (Doug Liman, 2010) and Green Zone (Paul Greengrass, 2010). But Argo contents itself with simply presenting the historical evidence and allowing the viewer to form their own opinion. By focusing on the human element, the film allows us to see the impact upon ordinary people of both revolutionary anger and capitalist greed. There may be some who bemoan any presentation of the CIA and US foreign policy as anything other than the epitome of evil – even a humanitarian mission like that undertaken by Tony Mendez (Ben Affleck) can be seen as an act of American imperialism and the Embassy fugitives should have been caught. I find this attitude unduly cynical and quite offensive – if we can feel empathy for the Iranian people then we can for the Americans who are equally victimised, ultimately by the same culprit. Or to quote Lester Siegel (Alan Alda), “Argo fuck yourself!”

Comedy

Satires about Hollywood range from the unnerving Sunset Boulevard (Billy Wilder, 1950) to the outrageous For Your Consideration (Christopher Guest, 2006). Argo accomplishes much that these films do and does so with neatness and economy, plus it has the bonus of being based on actual events. Lester Siegel and John Chambers (John Goodman) were a real producer and make-up artist in the 1970s, and Argo’s presentation of the lies, bluster and outright absurdity in movie-making is presented as both plausible and completely normal. This is crucial – rather than making Hollywood appear silly through caricature or stylisation, Argo plays it straight with simple presentation, again allowing the viewer to make up their own mind. I laughed out loud at several points during the Hollywood section of the narrative, such as Siegel’s anecdote about “knowing” Warren Beatty. Alda’s performance is larger than life which suits his character, and in a town known for frauds, fame and fantasy, he fits perfectly. The stages of film production are traced in all their showbiz glory, including the acquisition of a script, a cast reading complete with sci-fi costumes, and the more mundane office and (essential) advertisement in Variety. The cumulative effect of these scenes give the viewer reason to care that this film is produced – an interesting what-if would be for Argo to be entirely about the production of such a film; would the viewer’s investment been as high? I believe that it would – the passion and conviction of Siegel is infectious, and there is much to be enjoyed in the depiction of success, especially in such a weird and wonderful setting as Hollywood.

Thriller

While the Hollywood section of Argo is highly amusing, the bulk of the film follows thriller conventions, from the storming of the US Embassy and the escape of the six fugitives, to the final act when Mendez joins them and must lead them through Tehran. Argo delivers several highly tense set pieces – there were at least three points at which I let out a breath I had been holding. The casting helps: while Affleck is the biggest name in the film, the other recognisable faces – Goodman, Alda, Cranston – are all either in Washington or Hollywood. The fugitives in Tehran are all played by relative unknowns, so there is no star baggage to indicate who is more likely to live or die. Furthermore, the opening scenes establish these characters very well, thrust into a perilous situation. The sense of fear is conveyed through the combination of the performances and Affleck’s close, intimate cinematography, and also the ambient soundtrack. Shifting from hushed tones to eruptions of shouting, the atmosphere of omnipresent danger is almost palpable. I was struck by the sound of footsteps – hurried, on-the-verge-of-panic steps as they run from the embassy, and also voices – bustle in the market, discussions among the Revolutionaries at the embassy, and most of all in the breathlessly tense climax at the airport, when the fugitives are in most jeopardy.

Perhaps ironically, tension is exacerbated through the absence of violence. Not a single American agent fires a weapon in Argo, and despite the constant threat the film has few moments of actual violence. This places emphasis upon the actors and their fearful reactions, as well as those playing Iranians, especially Farshad Farahat as a checkpoint guard at Tehran Airport who is frightening when shouting in Persian, but terrifying when whispering in English. Similarly, the danger to the fugitives is increased through the (literal) piecing together of shredded documents, rather than men with guns chasing them. When armed men finally do chase the fugitives, it is all the more nerve-shredding for being the culmination of all the tension that has been built up previously.

Argo is also interesting as a period piece. I was struck by the moments in which Mendez or his CIA superior Jack O’Donnell (Bryan Cranston) communicate via landlines, diplomatic telephones and radios, as these contrast with the modern day equivalent where computers and cell phones are always within easy reach. It is surprising how much tension can be generated by the simple inability to contact the crucial person who will give the essential authorisation, and if the person is not beside the telephone, lives will be lost. The CIA desperately trying to find somebody without the advantages of surveillance cameras and electronic tracking could seem quaint and dated, but it actually increases the drama as it appears strange and alien in contrast to the high tech of James Bond, Jason Bourne and Jack Bauer (clearly, secret agents always have the initials JB). How do you get hold of the crucial person when they have no mobile and are not in the office to answer the phone? The resource used time and time again in Argo is creativity, a crucial element of intelligence that (at least on screen) can be lost in the jungle of technology. This resonates with the production of a movie, where creativity is needed at every stage, from script to publicity, creating another meta-cinematic link between the fiction spun by Mendez and the narrative spun by Affleck, and links Argo with a recent spate of nostalgic spy thrillers.

Nostalgia

Like the contemporary-set Skyfall (Sam Mendes, 2012) and the period features Munich (Steven Spielberg, 2005) and Tinker Tailor Solider Spy (Tomas Alfredson, 2011), Argo displays a nostalgia for old-style espionage, more dependent on individual resourcefulness and ingenuity than high-powered technology. Mendez’s mission is entirely dependent on subterfuge and his wits; despite the urgency of some situations, patience is also needed as an instant response may not come. Much as Skyfall features a steady stripping away of 21st century benefits, so Argo demonstrates a time, not so long ago, when high speed internet connections (which always seem so much more reliable for movie characters than for us mere mortals) were not the saving grace.

The nostalgia is established from the opening credits, which are presented with the Warner Bros. logo from the 1970s. There also appeared to be scratches on the print, which was impossible because I watching a digital projection. For there to be “scratches” means that the appearance of scratches had been added to the film data digitally, and this indicates a remarkable (and possibly excessive) commitment to the presentation of period. Historical context is not confined to what is represented but extends to the manner of presentation, creating an air of nostalgia that extends beyond the screen and into the auditorium itself.

Personally, I did not need digital scratches or an old style logo to draw me into the past. I was born in the same year as the Iranian Revolution so I remember scratches on celluloid prints and often found them irritating. Some lament the passing of projectionists and the rise of digital projection, but the presentation of a pristine image aids the illusion of looking through a window into another world, place or time. Scratches could interfere with engagement in the narrative, if one pays too close attention to the presentation. That said, after the opening minutes I was sufficiently drawn into the film that I didn’t notice any further scratches.

The nostalgia demonstrated in Argo, as well as the other films identified above, suggests a perspective on espionage and foreign relations that links back to the film’s political balance. By immersing the viewer within the context of the story, providing a potted history lesson and allowing the Iranian perspective as well as the American, not to mention emphasising the importance of Canadian assistance to the mission, Argo offers a perspective that is not only politically balanced but historically astute and remarkably multi-cultural. It is a tale of globalisation set in a time before globalisation was a buzzword. Rather than being a story of espionage for nefarious purposes, here the CIA saves lives and the casting of blame or identification of villains serves no purpose. All over the world, now as then, people are in danger and in terrible situations, often as a result of political decisions made by those who never have to experience the consequences. Argo draws attention to consequence and interconnections, and dares to suggest that international cooperation is a way forward, rather than individual nations and agendas.

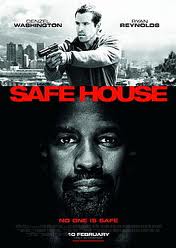

Review of 2012 Part One – “Safe House”

To break with tradition, I thought I’d start relaying my top ten of 2012 rather early. The main reason for this is that financial pressures have made it hard to see many films this year, so I’ve probably had my last cinema excursion of 2012. That said, there might be a December release that can be seen in January, so the official, ranked Top Ten will not appear until the start of 2013. But over the next few weeks, I’ll post commentary on the films that really impressed me this year. I have posted on several before, so I’ll try not to repeat myself, and those which have not been spoken on yet shall be in detail.

As a start though, I post on the year’s disappointments, as I don’t think I’ll see anything else that provokes my dismay. Overall, this has been a good year. I have very wide tastes so usually find something to appreciate in all movies that I see. There have been a couple of turkeys in which I did find something to appreciate, but they were still less than good. Terms such as “best” and “worst” are problematic because they imply some sort of objective standard, so in discussion I shall simply refer to what I found the weakest, the least convincing or the least entertaining films, and later on, what I consider the strongest and most impressive films that I saw this year.

Safe House (Daniel Espinosa, 2012) was a disappointment, mainly because its content was over-emphasised and therefore felt lacking in confidence. A film expresses confidence through pacing, measure and commitment to its subject. Safe House failed to deliver this confidence, through a plot that felt contrived for the sake of contrivance, characters that were thin at best, and a style that was terribly overwrought and more distracting than engaging. I’m all for a good conspiracy, but the conspiracy was so side-lined as to appear rudimentary. The film’s finale suggested some kind of wider socio-political critique, but this jarred against the mostly personal dramas of the earlier narrative.

The personal dramas were unconvincing as well. Denzel Washington is one of the finest actors working today, and he is as committed as always. But his Tobin Frost is neither sufficiently cynical nor idealistic. His poise and control demonstrates his experience and confidence, which results in him seeming to have walked in from another movie. I understand star vehicles, but could the vehicle and the star at least be going in the same direction? Frost’s relationship with Matt Weston (Ryan Reynolds) is meant to be the emotional core of the film, and Reynolds does a decent job of portraying the well-trained but inexperienced CIA operative. However, too much time is spent on the run for any real relationship to develop, and while some mentoring moments appear, they, along with too much of the film, get lost in the incessant, intrusive, infuriating unsteady cinematography.

The shaky cam aesthetic is one that can be used well, Paul Greengrass being a particular master of it with The Bourne Ultimatum (2007), United 93 (2006) and Green Zone (2010). Indeed, the cinematographer for Safe House, Oliver Wood, was also DOP on The Bourne Supremacy (2004) and The Bourne Ultimatum, which gave me a particular incentive to see it (although some were put off by the prospect of nausea-inducing cinematography). I did not find the shaky cam sickening, but it was very annoying due to its indiscriminate use. Weston sits and bounces a ball off the wall – camera waves around like the operator is drunk. David Barlow (Brendan Gleeson) and Catherine Linklater (Vera Farmiga) talk tersely at Langley – camera rocks around as though on board ship in a storm. Frost meets Alec Wade (Liam Cunningham) in a private restaurant booth – camera swoops around their faces and the confined space like a mosquito on speed. It got to the point where I wanted to shout at the screen: “Just stay still!” It was annoying to the point of disengaging me from the action completely.

When used judiciously, such as in sequences like Safe House’s car chases, one of which involves a struggle, as well as a fight at a second safe house, unsteady cinematography can be effective in bringing the viewer into the action and allowing us to vicariously experience the instability and disorientation of the action sequence. However, if the camera is constantly unsteady the viewer has no stability to be lost, is already disorientated, and therefore there is no suspense. Suspense is absolutely crucial to a thriller or action movie – the viewer requires uncertainty about what might happen in order to be engaged in the scene. Instability and disorientation can add to this uncertainty and increase the suspense, but when the opening shots and indeed all subsequent shots are unstable and disorientating, the viewer can be certain that what happens next will be unstable and disorientating! If you know what’s coming, suspense goes out the window.

Naysayers may point out that Paul Greengrass is similarly indiscriminate with his cinematography, but the crucial difference is pace. Greengrass maintains a swift pace throughout his films, Jason Bourne typically on the run while in Green Zone characters are either moving very fast or having quick, terse meetings. In United 93, the shaky cam is appropriate during the takeover and attempted re-taking of the doomed airliner, but earlier the camera stands back, only moving slightly as it betrays an almost voyeuristic pose as the hijackers offer final prayers and the passengers prepare to board. So Greengrass, champion of shaky cam, exercises its use with a surprising restraint and discipline, which Espinosa did not instruct Wood to do with Safe House. The dialogue scenes in Safe House are slower and more deliberate, working as a break between the action, yet the camera continues to pan, track, tilt, dip, sway, plunge, spin for no dramatic purpose. Get a Steadicam for the love of Hitchcock!

I like to assess a film on all its components, and I will say that the South African location of Safe House distinguishes it from the more standard American setting. But James Bond has been globe-trotting for 50 years, Jason Bourne passed through most of Europe as well as India and Russia (smashing a fair bit up along the way), and even Tinker Tailor Solider Spy (Tomas Alfredson, 2011) spent some time in Istanbul. For a view of a South African slum, you’re better off with District 9 (Neill Blomkamp, 2009). For a lean, tense espionage thriller with judicious use of shaky cam, you’re much better off with The Bourne Ultimatum.