Home » Posts tagged 'the dark knight'

Tag Archives: the dark knight

Ten Films for Ten Days – Day Seven

The seventh film in my list of ten significant films used to be among my top ten, and although it has been supplanted by another from the same director, this one still holds great significance for me. In 2000 AD, when this was released theatrically, I went through some bad times in which I felt that the majority of people were against me and that an institution I believed in was going to the dogs. Therefore, Ridley Scott’s epic tale of a general who became a slave, who became a gladiator, who defied an emperor, struck a deep, resonant chord with me. I went to see Gladiator five times on its original release, that’s right, five. While I have seen other films as many or more times in the cinema, those were due to re-releases and special screenings (yes, The Dark Knight, I mean you). ‘Gladiator’ offered me hope, inspiration, catharsis and the other positive feelings that one gets from bloody hand-to-hand combat and the deep-set rot of a once noble empire.

The talent behind Gladiator have to an extent gone off the boil. Russell Crowe was a known figure but became a star and an Oscar winner with this film, while Ridley Scott came as close to an Oscar as seems likely. Their subsequent collaborations such as American Gangster and Body of Lies failed to bottle the lightning of Gladiator. That said, it is fair to say that Joaquin Phoenix has become a more respected presence as time has gone by, not least by seeking out interesting projects from Walk The Line to The Master to You Were Never Really Here. Writer John Logan recently did us all proud with the excellent TV series Penny Dreadful, and The Martian demonstrated that Scott still has some decent work left in him (the less said about The Counsellor and Alien: Covenant, the better). But Gladiator remains undimmed in its epic grandeur, an awesome spectacle that works on a pure visceral level and has moving emotional depth. Furthermore, the film makes interesting comments about the proper uses of power and even our own violent appetites. Are you not entertained? I certainly am.

Wonder Woman

Amidst the problems of Batman V Superman: Dawn of Justice, one pinnacle of wisdom, class and super-powered kick-assery stood tall above everything else – Gal Gadot’s Wonder Woman/Diana Prince. Despite this appearance and over 70 years of comic book history, the world’s most famous superheroine has waited until 2017 for a solo big screen appearance. Happily, Wonder Woman is worth the wait, as director Patty Jenkins delivers a dynamic, inventive and witty superhero adventure of duty, will, the pervasiveness of evil and the power of love. From the wraparound story in modern day Paris to childhood and training among the Amazons of Themyscira, Jenkins, Gadot and screenwriter Allan Heinberg draw the viewer into Diana’s world, sharing her joys, fears and discoveries.

Rather than following the dour example of Zack Snyder’s Man of Steel and BVS: DOJ, Wonder Woman is more reminiscent of Captain America: The First Avenger with its period setting and also Thor with its dramatisation of myth, and shares a sense of fun thus far lacking in the DC Extended Universe. Diana becomes aware of the wider world when American spy Steve Trevor (Chris Pine) arrives with WWI German soldiers in hot pursuit. From here we embark on a ride to London and thence to the Western Front, a ride that is jaunty, gripping and at times powerfully moving. Jenkins strikes a fine balance between fish-out-of-water comedy, both for Steve among the Amazons and Diana among the British, grim moments featuring the impact of war on civilians and the ruthless aggression of General Ludendorff (Danny Huston), and some truly magnificent action set pieces. These set pieces constitute major developments of the drama: the first exhibits the skill and power of the Amazons; the second demonstrates Diana coming into her own as a warrior and had me welling up with emotion; the third begins with a gritty physicality before escalating to truly epic proportions. A common criticism of superhero films is that the final act succumbs to CG overload, but in the case of Wonder Woman the onslaught of visual effects expresses narrative development and the characters’ discoveries.

This climactic sequence also features the film’s greatest strength: acknowledgement of the pervasiveness of evil. Throughout the film, Diana believes that it is her mission to destroy Ares, the god of war, because this will end the Great War, a belief that Steve and the rest of their notably diverse team find naïve. A central villain is common to superhero cinema and often the purpose of the narrative is to defeat him (or occasionally her), but the more challenging entries in the genre such as X-Men, The Dark Knight and Logan do not locate evil quite so easily. Diana’s journey of discovery is also that of the viewer in realising that this film is doing something a little different, and the joy of this difference alongside the electrifying action makes the film into something special.

Furthermore, Wonder Woman makes good on its gender politics. Diana is a superb character, defined not as a woman but as a warrior for justice. The film therefore manages to present that elusive thing called equality, where men and women unite for a common cause because they all care. Furthermore, the absurdities of patriarchy are highlighted, such as when Diana encounters the British high command in London and is dismayed by their lack of compassion, in stark contrast to the nobility of the Amazons. Some might find the romance between Steve and Diana clichéd and disappointing, but it is important to note that their relationship is part of a larger conceit of love that pervades the entire film, from the bonds among the Amazons to those between Steve’s fellow soldiers, and the compassion and empathy that drives Diana throughout. Superhero movies are often concerned with hope, but Wonder Woman goes further, Jenkins crafting a thrilling and moving tale of the compelling and invigorating power of love for all humanity.

Top Ten Directors – Part Three

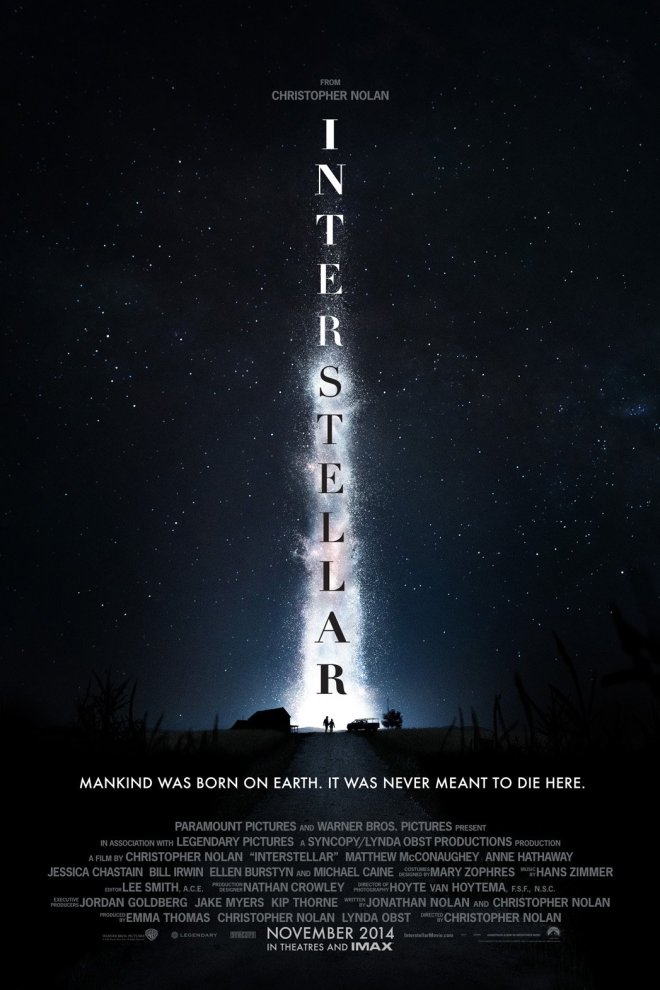

Following my review of Interstellar, I thought it time to discuss another of my top ten directors. Christopher Nolan has had an impressive ascension through the hallowed halls of Hollywood, attaining a position similar to those of previous directors I have written on, Steven Spielberg and James Cameron. All of these filmmakers are able to make distinctive, personal films within the institution of Hollywood, films that bear their unmistakable stamp.

Nolan’s progress has been remarkable – in fifteen years and with only nine films to his credit, he is now a marketable brand. This is evident in the publicity campaign for Interstellar: posters and trailers emphasise that the film is FROM CHRISTOPHER NOLAN, relying upon the director’s name rather than that of the stars as is more common practice. This is surprising considering the bankability of the principal actors of Interstellar – while their names appear on posters, they are not mentioned in trailers and there is no mention that these are Academy Award Winner Matthew McConaughey, Academy Award Winner Anne Hathaway, Academy Award Nominee Jessica Chastain and Academy Award Winner Michael Caine. Publicity for other recent films featuring these actors has emphasised them, but in the case of Interstellar, the director is used as the major selling point.

This emphasis upon Nolan has grown over his career – publicity for Insomnia mentions that the film is from THE ACCLAIMED BRITISH DIRECTOR OF MEMENTO. Similarly, publicity for The Prestige describes the film as being FROM THE DIRECTOR OF BATMAN BEGINS AND MEMENTO.

Both these films, however, were largely sold on their stars, while Batman Begins and The Dark Knight are simply promoted as Batman films. Following the success of The Dark Knight and Inception, however, The Dark Knight Rises and Interstellar declare the director; these films are FROM CHRISTOPHER NOLAN. What then, does this publicity refer to?

The Nolan brand is one of major releases of ever-increasing size, and with particular emphasis upon complexity – in short, brainy blockbusters. If the Spielberg brand is one of sentimentality then Nolan’s is intellectual – here is the filmmaker who makes you feel intelligent (if you can make head or tail of his films). While this is unfair to Spielberg, whose films are often as complex as they are sentimental, Nolan’s films consistently display interests in time and identity, and utilise elaborate editing patterns that confuse and delight in equal measure. This has led some reviewers to describe the director as chilly and unemotional, more interested in calculation than feeling. This seems strange when considered in light of the consistent interest in loss and grief that runs through Nolan’s oeuvre. Consider the grief that drives Bruce Wayne in Batman Begins and perverts Harvey Dent in The Dark Knight, as well as Cobb’s haunting guilt in Inception and the tragic self-perpetuation of Memento, not to mention the parent-child relationship that runs through Interstellar. Nolan’s films are driven by the emotional torment of their protagonists, and the various narrative and stylistic tricks all serve this central conceit, taking the viewer into the emotional state of the characters through a dazzling mastery of the cinematic medium.

For all the scale and grandeur of Nolan’s blockbusters since Batman Begins, it is Memento that I pick both as my favourite Nolan film and the best introduction to his oeuvre. This is not to say that Nolan has lost his way or his interests and concerns have been swamped by bloated budgets and studio demands, but Memento’s deceptive complexity rewards repeat viewings and endless discussion (having taught this film several times on a film-philosophy course, I have repeatedly found this to be the case). Memento’s chronological rearrangements express the subjectivity of memory and knowledge, and the lack of certainty over what is presented at face value, while the presence of tattoos highlights the (unreliable) use of embodiment to fix oneself in the world. The ethics of revenge and personal goals are questioned and answered, and those answers are then questioned afresh. And the emotional core mentioned above provides the film with a deeply tragic dimension that leaves the viewer unsettled, both sympathetic and uncomfortable towards the protagonist Leonard (Guy Pearce). This ambivalence has continued throughout Nolan’s work, and while Memento may not be the most ambitious work in his oeuvre, it remains an enthralling and compelling introduction to the work of this distinctive and singular director.

Disappointing Instalments

Spoiler Warning

I recently had a conversation with a friend about recent films that we had different responses to, Kick-Ass 2 (Jeff Wadlow, 2013) and The Wolverine (James Mangold, 2013). I found both of these disappointing and my friend thought they were alright. In the case of Kick-Ass 2, my fellow conversant knew that it would not surprise or shock them like the first, and that the only way it could have done would be to change the style of the film. Therefore, the film was enjoyable as an extension to the first, but nothing more. The absence of Big Daddy (Nicolas Cage) was felt, and my friend commented that the story did not have enough suspense, unlike Matthew Vaughn’s original.

Both of us agreed that Hit Girl/Mindy McCready (Chloe Grace Moretz) was the best thing in Kick-Ass 2, so for me, it was disappointing that she was underused and spending time becoming a ‘regular girl’, only for her to abandon that and re-embrace Hit Girl. It is a common trope in superhero narratives that heroes renounce their super identities (see Superman II [Richard Lester, 1980], Spider-Man 2 [Sam Raimi, 2004], The Dark Knight Rises [Christopher Nolan, 2012]), but it tends to be more traumatic and a crisis of identity. Had Kick-Ass 2 focused on that element, it would have been more effective, even as an identity crisis within high school. High school is fertile ground for dramas about identity and finding oneself, so a high school action comedy about Hit Girl would have a lot of potential.

Unfortunately, with Mindy/Hit Girl side-lined, Kick-Ass 2 lacks not only suspense but emphasis, wavering between Dave Lizewski/Kick-Ass and his ongoing ambition, as well as Colonel Stars and Stripes’ (Jim Carrey) Justice Forever band, and the increasing villainy of Chris D’Amico/The Motherfucker (Christopher Mintz-Plasse). The film therefore lacks focus and a coherent theme, essentially trying to play off the original’s feature of having superheroes swear and get badly hurt. But in Kick-Ass, that was a point rather than a gimmick. In Kick-Ass 2, it’s just a gimmick. There are some good sequences, including the final battle and indeed most scenes involving Mother Russia (Olga Kurkulina), and I liked the suggestion of a romance between Mindy and Dave, but overall, the film felt lightweight and uncertain of its meaning.

It used to be the case that sequels were never as good as the originals. Superhero films especially buck that trend, with Spider-Man 2, Blade II (Guillermo Del Toro, 2002), X-2 (Bryan Singer, 2003), The Dark Knight, maybe even Fantastic 4: Rise of the Silver Surfer (Tim Story, 2007) improving what came before. Sadly, it seems that Kick-Ass 2 is what we used to expect from sequels.

The Wolverine is another matter. The X-Men franchise has been very patchy, at its best striking a balance between personal dramas, thrilling action and wider ramifications. The wider ramifications was the major missing feature from The Wolverine, as it is the most intimate and personal film of the franchise thus far. Director James Mangold has a talent for intimate, down-to-earth drama, whether that be the biopic melodrama of Walk The Line (2005) or the terse psychological thrills of Identity (2003). The Wolverine demonstrates that he can still deliver the necessary action spectacle (although perhaps that should be credited more to second unit director, editor and the special effects team), but despite the bullet train sequence and the final battle with Silver Samurai, The Wolverine is remarkably unremarkable, because there seems to be little reason for what is going on. It is essentially the further adventures of Logan, revisiting an old friend, making new ones including a requisite new romance, and I was left thinking ‘So what?’ The spectral presence of Jean Grey (Famke Janssen) was unconvincing, and the most moving moment was Logan’s early communion with a wounded bear. It could have been refreshing to see Logan more vulnerable, like those mentioned above it is an instance of the superhero losing their powers, but the trope of him having to adapt to being hurt was not given enough variety, swiftly becoming repetitive.

To make matters worse, the villain of The Wolverine was very uninteresting, Viper (Svetlana Khodchenkova) little more than a mutant riff on the vicious beauty, which was done far more interestingly with Mystique (Rebecca Romijn/Jennifer Lawrence) and Emma Frost (January Jones) in previous installments. Perhaps if she had been in a position to fight Logan herself, like Lady Deathstrike (Kelly Hu) in X-2, it might have been interesting, but instead she is far from a worthy adversary. The final clash between Wolverine and Silver Samurai was flashy but felt more like an obligation than an organic development, while the sudden reappearance of the bone claws was overly convenient.

Overall, The Wolverine felt lightweight, nothing attached to what was going on. For me, the X-Men films have been most enjoyable when the stakes are high, which they have been previously:

X-Men – the irradiation of the world leaders

X-2 – the death of all mutants and, subsequently, the death of all humans

X-Men: The Last Stand – the ‘cure’ for mutation

X-Men Origins: Wolverine – more personal, but still a campaign against mutant-kind

X-Men: First Class – the Cuban missile crisis and World War Three

The Wolverine – dying man wants to live forever and will steal Logan’s ability to heal so that he becomezzzzzzzzzzzzzzzz

The stakes of The Wolverine are too low and, therefore, the film lacks drama. Ironically, the biggest problem with The Wolverine is the best thing in it – the mid-credits sequences featuring Professor X and Magneto. I had read that Patrick Stewart was going to cameo, but I was not expecting Ian McKellen to show up as well. In addition, the foreshadowing of Trask Industries is another nice detail, demonstrating economic storytelling and raising expectations. I eagerly anticipate X-Men: Days of Future Past (Singer, 2014), combining the elements established in earlier instalments into something both new and familiar. But when the best thing in a film is a scene with no connection to what went on before, then the film as a whole is clearly doing something wrong.

Bat Memories Part Two: The Dark Knight That Rises In Us All

A little late, I complete my ruminations on the cinematic excursions of the Caped Crusader, with consideration of how Christopher Nolan and his collaborators re-constituted Batman after the quality vacuum that was Batman & Robin, as well as offering my thoughts on The Dark Knight Rises.

When I read that the reboot of the Batman franchise was to be directed by the man behind Memento and Insomnia, I was pleased because those films impressed me (indeed, Memento clarified that my favourite type of film is a good thriller and I haven’t gone wrong with that approach yet). Just how impressive Batman Begins turned out to be took me (as well as others) quite by surprise. Not only did Nolan (along with brother/co-writer Jonathan, as well as David S. Goyer, DoP Wally Pfister and producer/wife Emma Thomas) deliver a detailed, consistent and plausible reboot and reinterpretation of the Batman mythos, they also created the best superhero movie made up until that point. The superhero sub-genre had been growing since Blade in 1998, got better with X-Men in 2000 and really exploded with Spider-Man in 2002. Blade II, X-2, Daredevil, Hulk and Spider-Man 2 followed in quick succession, so when Batman Begins arrived in 2005 (along with Fantastic Four), the superhero stage was already crowded.

What Batman Begins managed to do was delve deep into the psychology of a superhero figure, and strike a balance between character interplay and thematic exploration with spectacular action. Not that others had not done this as well – Spider-Man 2 and X-2 especially have plenty of action and plenty of character – but Batman Begins actually made the action sequences the least interesting parts of the film. Which is not to say they were bad: the explosive escape from the League of Shadows’ lair; Batman’s first appearance at the docks; the attack on Wayne Manor; Batman’s rescue of Rachel Dawes and the finale in the Narrows and aboard Gotham’s elevated train are all masterfully handled set pieces. In a year when Spielberg’s War of the Worlds was more Run of the Mill, and Lucas’ Revenge of the Sith went too far into CGI flamboyance, it was most refreshing to see a relatively new director stake such a claim in the blockbuster field. Yet despite the impressive set pieces, the inter-personal dramas between Bruce and Alfred, Jim Gordon, Ra’s Al Ghul and the Scarecrow, as well as the careful development of the Batman persona, make Batman Begins a remarkable investigation into identity, in relation to one’s own ideology, family background and social position, not to mention a varied exploration of the theme of fear. No other superhero film managed to accomplish so much and so efficiently.

With the superhero genre effectively deconstructed and reconstructed, Nolan could go to strange new places with the sequel, which is why The Dark Knight feels like something different and special. It is a superhero film only by virtue of having names, costumes and a few gadgets; otherwise, it is effectively a straight crime thriller. Except it is also more than that, as crime thrillers seldom have a criminal as malevolent and uncontrollable as the Joker. The Joker truly is the trump card in The Dark Knight, as discussions of motivations and objectives go out the window: as Alfred tells Bruce (and as we were warned in the teaser trailer), “Some men just want to watch the world burn.” Nolan shows us the world burn in The Dark Knight – rather than Batman being a resource for law and order, Gotham becomes more violent and chaotic than ever. Much of the Joker’s power has been credited to Heath Ledger’s incendiary performance, but both as a character and an element within the plot the Joker serves to elevate the film into a thought-provoking philosophical discussion on chaos and order. The most dramatic sequences are, again, dialogue scenes such as the confrontation between Batman and the Joker in a police interview room, which infamously turns into a torture sequence, as well as the final stand-off between Batman, Gordon and Harvey Dent. That these sequences stand out despite the tremendous opening bank robbery, the gripping battle between massive truck and Batmobile/Pod, and the high rise assaults in Hong Kong and Gotham, is testament to Nolan’s mastery of the cinematic craft, blending high octane thrills with serious themes and characters that can explore these themes in uncompromising ways. More than the best superhero film ever, The Dark Knight is a true genre-blender, merging elements of crime and political thrillers into a potent and compelling cocktail.

It would be fair to say that my reaction at the end of The Dark Knight Rises was one of relief: relief that it managed to live up to expectations. It did not supersede them – I think after the extraordinary nature of The Dark Knight, the expectation that it would be topped was unreasonably high. However, being aware of this, my hope was simply not to be disappointed, so I was relieved not to be. Earlier this year, my local world of ciné were nice enough to screen Batman Begins and The Dark Knight in a single programme, so I got to see both on the big screen again before The Dark Knight Rises. Therefore I was well prepared to compare Christopher Nolan’s trilogy climax to his previous instalments.

The Dark Knight Rises succeeds as a trilogy closer because it builds upon yet does not deviate from what came before. We have much of the same: Alfred being regretful, Bruce being committed, Lucius being supportive, Gordon being fretful, and we have much that is new: Selina being deceitful, Bane menacing, Blake simultaneously idealistic and realistic, and Miranda being vengeful. I also expected Nolan’s remarkable ability to deliver superb action sequences, yet make these sequences the tip of the iceberg, two characters talking being even more dramatic than attack vehicles shooting at each other. Combining the two is effective as well: Bane and Batman taunting each other while they fight helps to draw the viewer in, feel the emotional as well as physical blows. Speaking of emotional blows, it was on the second viewing that I actually welled up during Alfred’s final speech, as he grieved for the Waynes and told Bruce’s parents how sorry he was that he failed to protect their son. Clearly, the film was powerful.

A key part of this power, like the previous installments, are the ideas that feature so heavily (but not heavy-handedly) in The Dark Knight Rises. Slavoj Zizek gives a very interesting discussion on the politics of the film, concluding that it is in some ways impressive and in others ham-fisted. Other reviews comment on the film’s engagement with the Occupy Wall Street movement and the potentially disturbing politics the film suggests. For me, a great element of the trilogy as a whole and its finale in particular, is the presentation and engagement with a debate over a type of heroism that is surprisingly egalitarian.

In my last post, I discussed the failures of the previous Batman movies to deliver a truly compelling take on the Dark Knight. I think a key reason was a specific failure to explore the character of Batman/Bruce Wayne in much depth. Crucially, this was what Nolan indicated he would be doing with his reboot of the franchise, so that was another reason I had high hopes for this re-interpretation.

When first conceiving of his vigilante persona in Batman Begins, Bruce describes an incorruptible symbol. Alfred tells Bruce in The Dark Knight what the “point” of Batman is: “He can be the outcast, no one else can”. For Nolan/Bale’s Batman, that is indeed the point of Batman, he can be and do what no one else can. In The Dark Knight Rises, Bruce explains to John Blake and Jim Gordon that Batman is a demonstration that anyone can be a hero. I think this may be the reason Batman has always resonated with me, and why my work on the character thus far has focused upon discussions of heroism. Nolan’s trilogy is distinguished from the previous interpretations of the Dark Knight through its emphasis on “realistic” feats and devices rather than more outlandish events in such franchises as Spider-Man (Raimi and Webb) and The Avengers. Critics have pointed out the implausibility of such features as the Bat, Bruce’s trip from wherever the prison was back to Gotham without passport or money, and Selina Kyle’s heels, but nonetheless the films still take place in a world far-removed from genetic mutations into lizard creatures and devices that open portals to distant parts of the galaxy. However, being closer to our reality extends beyond the gadgets and the vehicles.

In my previous post, I argued that Batman Forever impresses me the most of the earlier Batman films, because we have an internal and external struggle for Bruce Wayne. This dramatic tension is played out on a far wider scale across Nolan’s Dark Knight Legend, as we focus upon Bruce’s attempts to deal with his past, present and future. Batman is a form of therapy, but ultimately lacks catharsis: he can make a start of helping the people of Gotham, but when it all goes horribly wrong in The Dark Knight, he gets stuck, as Alfred identifies, he never moved on. Yet by the end of The Dark Knight Rises, he has moved on, “rising” out of the pit of depression that made him a recluse by the start of the film.

Bruce’s rise is only one of a number of appearances of the trope of rising in the film. Once imprisoned by Bane, Bruce literally rises out of the hole in which he is imprisoned, as did the previous inmate of the prison, whom both viewer and protagonist believe to be Bane, but turns out to be Talia/Miranda. The components of Bruce’s lair rise out of the water in the Batcave, a walkway rising under Alfred’s feet as he approaches his master/charge. In his final act of sacrifice, Batman rises out of Gotham in order to carry the bomb out of harm’s way. This final rise is also Bruce’s way of moving on, as he effectively “kills” Batman. The film’s finale might have benefitted from the ambiguity of not seeing the reverse shot of Alfred’s POV in Florence, when he sees Bruce and Selina, free of Gotham, but I choose to believe it is what he sees, allowing us the viewers to share in the catharsis of all three characters: all have risen from the darkness, the anguish and the pain that we have spent three movies sharing with them. How fitting that we share their rise as well.

Metaphorically, not only does Bruce rise out of isolation, but Batman rises from the state of pariah, and Gotham must rise above the state of martial law imposed upon it by Bane. Selina rises from cat burglar to freedom fighter, James Gordon rises from the depressed and injured state that he has fallen into, while John Blake rises from the rank of uniformed cop to something more distinguished. Indeed, the final shot of the film both presents and expresses rising, as it is filled by the platforms of the Batcave, rising with Robin Blake (the new Dark Knight?) upon them, literal and metaphorical rising encapsulated in a shot that both ends this legend, yet allows us to imagine what more could happen.

This, perhaps, is the final point of Batman: we can all be heroes in one way or another. We need not put on costumes or fight crime, but “A hero can be anyone. Even a man doing something as simple and reassuring as putting a coat around a little boy’s shoulders to let him know that the world hadn’t ended.” So perhaps that is the message we can take from The Dark Knight Legend – whomsoever, in whatever circumstances, helps out fellow people, is a hero. That is the power of the Dark Knight Legend, taking the idea of heroism seriously, both as a dramatic device, and as an in-depth thematic exploration. To that height, Nolan rose, and certainly delivered me the Batman I always wanted.