Hellraiser

Hellraiser is an odd duck. While not particularly scary it is fascinating and rich. Clive Barker’s tale of the line between pleasure and pain, as well as the line between dimensions, features some awkward locations as well rather stilted performances. It also delivers some remarkable production design and truly iconic make-up, cementing its position in body horror. Metal hooks into flesh as well as erupting bodies may seem a little dated now, but Barker creates effective atmosphere, especially during the brief appearances of the Cenobites. Skilful lighting and ample use of dry ice create a sense of the otherworldly, and the uncanny appearances of the ‘explorers in the further regions of experience’ are recognisably human and yet very overtly other. Tapping into fears from films as diverse as Us and The Fly, there is something very wrong about these creatures.

Despite the extreme moments, the film ties the horrific images and events to domesticity, drawing on the well-established trope of family being the ultimate horror. The family home makes an effective site for the film’s visceral horror, where the idea of skeletons in the closet gets taken to a literal and decidedly squishy level. What Hellraiser says about home, body and mind is unsettling and enduring. To see the distorted bodies of Frank (Oliver Smith) as well as the Cenobites is as fascinating as it is repulsive. What could that possibly feel like? To quote another iconic Barker creation, the pain must be exquisite. As is often the case, horror acts as a cautionary tale about going too far, while also expressing our innate desire to do exactly that.

Turning Screws Part Four

In a previous post, I discussed The Haunting of Bly Manor in terms of character and highlighted that it is a very melancholy show. How is it as a horror? Is it scary, or at least unsettling? I can confirm that it certainly is. Maybe not as petrifying as The Haunting of Hill House, but the production design and cinematography create an environment that is enclosing to the point of claustrophobia. This is quite a feat considering the expansive spaces of Bly Manor. The grand kitchen and dining room, where much of the action takes place, is homely and pleasant. The bedrooms as well as the entrance hall and living room are similarly tasteful, and yet the ornate panelling seems imbued with the regrets of the past. These regrets also manifest as figures that appear in the background, with little or no emphasis which may leave the viewer wondering if they were really there.

This is one of the show’s most unnerving features. At many points we see someone in the background, but the characters do not and, more importantly, with no visual emphasis it creates an untrustworthy situation. How can we trust what we see when the visual text we read presents us with something that has apparently no reason to be seen? In this way, the show becomes uncanny – both familiar in terms of the tropes of the ghost story, yet unfamiliar in that we don’t know why these figures are there. But creator Mike Flanagan and his collaborators are playing the long game, and although the first few episodes are a little shaky, as the series comes full circle everything starts to fit together.

As events unfold, the tragedy becomes clearer and the scares more overt. There is a facial effect that is especially unnerving, as the ghosts are again recognisably human but seriously inhuman. The single most frightening thing in the show is the Lady in the Lake (Kate Siegel). No swords here, but plenty of choking and drowning, including a moment with a dress that deserves mention alongside In Fabric. Furthermore, the effect of drowning is notable, presented as tragic and terrifying all at once. Sometimes the show conveys drowning in horrific detail, complete with a heartbreaking aftermath. At other points, we see characters immersed where water should not be, perception and experience created through an astute blending of visual and aural devices.

The presentation of drowning, and the wet legacy that it leaves, is among the show’s scariest features. But it is also one of the most emotional and part of what is perhaps the show’s greatest strength: putting memory on screen. Film – be it cinema or TV – can replicate the experience of memory and dreams through cuts and sudden juxtapositions that startle but are nonetheless understandable. The Haunting of Bly Manor does this extraordinarily well. Referred to as characters being ‘tucked away’, scenes are played and replayed, much as ghosts appear and disappear. Memories are thus like ghosts, emerging unexpectedly and without warning. Sometimes this is horrific, as we recall a traumatic memory. Other times it is tragic, such as the recollection of lost loves. Taken as a whole, the structure of the show proves itself to be quite ingenious as, despite the episodes having different directors, visual and narrative cues are consistently connected. Even the overall framing device proves to have great emotional weight. Come the final coda and explanation of everything we have seen, you may have had some shivers, but you could also be wiping away a tear or two.

FrightFest

I’m a little busy this weekend due to FrightFest 2020. It’s an online festival but I’m seeing and reviewing quite a few films. These reviews will appear on the review site, the Critical Movie Critics. In brief though, so far I’ve seen four films, and my views are:

A suffusive, sensual and seriously sinister blend of repression, rebellion, teen terror and occult horror.

A slow burn, drip feed delivery of menace and dread, repression, deceit and the uncovering of deep, dark secrets.

A sumptuous, handsome and bloody but clumsy, campy and ultimately unconvincing mishmash of folk horror, history and action.

A garish, confused and awful muddle of genre tropes, wretched people and nonsensical ideas around fame, recriminations and stupidity.

More to follow, as HorrOctober continues!

Turning Screws Part Three

What does it mean to be haunted? In ghost stories, the spirits of the departed often serve as metaphors for memories and regrets. In our own lives, we are haunted by memories and regrets. Lost loves, past traumas, choices we made – all of these haunt us in the sense that they are gone and yet linger in memory. Therefore, haunting refers to a peculiar relationship with time, one that does not work in a strictly linear way. Our bodies may move through time in one direction and at a constant rate (gravity fluctuations notwithstanding), but our consciousness, our awareness, flits back and forth in time. As we are conscious of past moments, those moments haunt our present.

Haunting as a flitting of consciousness is central to The Haunting of Bly Manor, a nine-part Netflix series by Mike Flanagan that adapts the works of Henry James. It is both a ghost story and a love story, although this is not immediately clear. In ‘Episode One: The Great Good Place,’ a wedding guest (Carla Gugino) in 2007 begins a ghost story, which will sound familiar to those who know The Turn of the Screw and The Innocents. Flashing back to 1987, an au pair is hired to work in a remote English country house, where she will care for two orphaned children. Upon arriving, American Dani Clayton (Victoria Pedretti) encounters increasingly weird and frightening events.

Adapting James’ 1898 novella into the 1980s necessitates some changes. 1987 is well-evoked (and makes me feel my age!), and the series’ treatment of class is notable in that divisions are present but less overt than would be the case in an earlier period. More significantly, the scope of this series allows the writers to flesh out all the characters, making the show a great ensemble. Attention to character also serves the central premise of haunting as memory. The narration by the Storyteller demonstrates the persistence of memory, and within the 1987 story we get further flashbacks which detail the lives of the characters at Bly Manor. These stories are both tragic and disturbing, from Miles’ (Benjamin Evan Ainsworth) school experiences to Dani’s trauma to possibly the peak of the series as a whole, ‘Episode 5: The Altar of the Dead’, when we the times of Hannah Grose (T’Nia Miller). This episode highlights the series’ motif of repeated action, which becomes steadily more apparent and creates a proper mystery in ‘The Altar of the Dead’, before delivering a devastating climax which throws the whole of the story into a different light.

Prior to that point, ‘Episode 4: The Way It Came’ has been emotionally powerful, delivering a progressive twist on the Gothic trope of a woman not trusting her mind. Dani repeatedly sees some sort of spectre which is framed in such a way as to be a memory rather than something supernatural. Hence, when we learn what this ominous figure with shining eyes means, it carries significant emotional weight as well as explaining Dani’s distressed but not disturbed mind. Further progressive elements in the series are a racially diverse cast and a queer relationship. These elements are not emphasised but simply presented as natural, as indeed they should be. ‘The Way It Came’ is also desperately sad and emphasises the melancholia of haunting and indeed mortality. A speech by Owen (Rahul Kohli) had me shed a tear, and the revelations of ‘The Altar of the Dead’ made the melancholia even stronger. It’s a fine ghost story that has you both jumping and weeping in quick succession. I’ll say more about the jumps and dread next time.

Turning Screws Part Two

Expectations are a hard thing to live up to. If you hear something is bad, you have lower expectations and may be pleasantly surprised. If you hear something is good, there is a risk that it will not measure up. As I have become more versed in horror, The Innocents comes up as one of the greatest ghost stories ever filmed, a major influence on later entries in the sub-genre such as The Sixth Sense, The Others and The Orphanage. Yet despite this, it took me a long time to get around to watching The Innocents, and when I did, I feared it would not live up to its reputation.

Holy haunted houses, did it ever! Jack Clayton delivers a masterpiece of atmosphere, creeping dread and suspense, that simultaneously could have created every trope of the ghost story and then pushed them to their logical extreme. The setting is sublime – an imposing manor house so steeped in its grounds as to be isolated from anywhere else. Within these grounds, curling mist envelops trees, buildings and people alike, turning Bly Manor into an eerie space between dream and reality. Within this space, Miss Giddens (Deborah Kerr) forms a constant anchor for the viewer, her encounters with the uncanny prompting fearful responses in us as much as her.

Central to this uncanny element are the creepy kids, Miles (Martin Stephens) and Flora (Pamela Franklin). Diminutive yet precocious, both children seem as much out of time as the house itself. Miss Giddens’ devotion to them is admirable and understandable, her relationship with them crafted in a way that is more nuanced and relatable than the idealisation and naivety of that in Henry James’ novel. Within the manor’s cavernous space, the children appear out of shadows as well as shafts of light, seemingly a manifestation of the house’s unsettling atmosphere, much like the mysterious appearances of Miss Jessel (Clytie Jessop) by the lake and Peter Quint (Peter Wyngarde) in the window.

Beautifully, Clayton maintains an extraordinary ambiguity throughout, never clarifying if what we see is actually supernatural or the product of Miss Giddens’ mind. This is a familiar trope of the gothic and the ghost story, presenting the woman who either is hysterical or is driven to hysteria by her environment. In this case, however, Clayton never allows Kerr or the film as a whole to tip into full-on hysteria. Set pieces escalate slowly but surely, with jump scares developing out of the overall sense of unease. Therefore, the film keeps us aligned with Miss Giddens’ perception and denies access to certainty. Is she/we seeing ghosts and encountering possession, or is she imagining things (which we also see) because of the isolation and the unusual but not necessarily supernatural events? As I have suggested previously, this may be the greatest fear of all – the inability to trust one’s own mind. Clayton injects that fear into the viewer’s own mind, so we are not sure what happened. Just at the point where the strange events might have been confirmed one way or another, the film ends, leaving us with another mighty trope of the ghost story – melancholia. Brought on by grief, Miss Giddens and the viewer is left with misery, and the lingering guilt that makes fear all the worse.

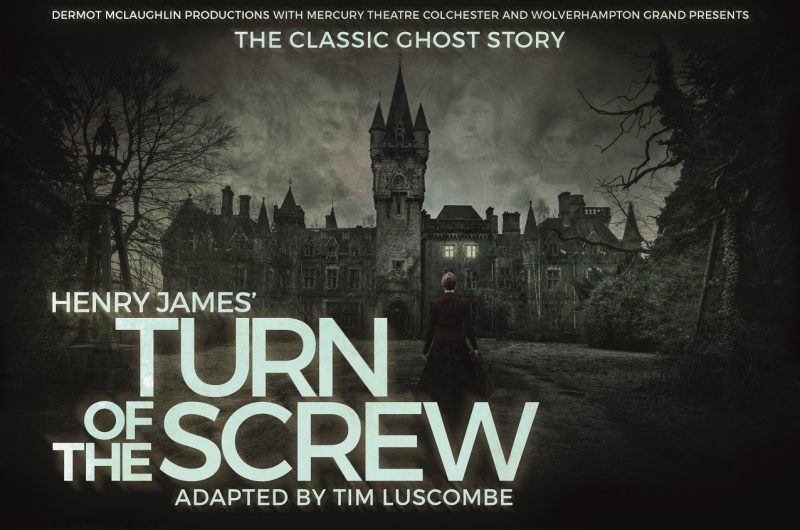

Turning Screws Part One

Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw from 1898 is an iconic and much adapted piece of gothic/horror fiction. This year, I encountered three significant versions: James’ original novel, the 1961 film The Innocents and the 2020 Netflix series The Haunting of Bly Manor. I’ll discuss all three this week.

Beginning with the novel (yes, I read books too, shocking!), I confess I was disappointed. The premise of The Turn of the Screw is intriguing enough. An isolated mansion, orphaned children, absent uncle, mysterious deaths, young woman who doubts her surroundings and, increasingly, her sanity. Along the way there are some unsettling moments, such as the face at the window and of course the precocious and creepy children. There are some vivid descriptions that provoke a sense of dread, and it’s easy to see why this story has loaned itself to adaptation over the years.

Unfortunately, James undercuts his tension through a cyclical structure to the point of tedious repetition. The governess’ encounters with the uncanny events of Bly Manor are recounted to Mrs Grose, and then we have another encounter and another recounting. The relationship between the governess and the housekeeper seems the core of the novel, with the children more like objects of mystery than subjects of agency. Indeed, the gradual discovery of Miles’ strange association with Peter Quint forms the thrust of the narrative, leading to an admittedly powerful conclusion. It’s just a shame that James was rather unimaginative with the journey to get there.

Lake Mungo

Ignorance can be useful. After hearing some recommendations, I checked out Lake Mungo. I knew nothing about the film other than the title and that it was an Australian horror. From this scant information, I theorised that it would be an outback monster film, perhaps like Rogue or Primal, or a hickspoiltation like Wolf Creek. As a result, I was unprepared for the blend of documentary footage, news reports and found footage that constitutes the movie. The narrative and aesthetic had me believing I was watching a documentary about a bereaved family and the possibility of a haunting, one that was both melancholic and unsettling.

The copious found footage, especially the son of the family being into photography, seemed rather convenient. However, it makes sense that the film was only made because of this available material, the director learning about a family who had suffered a bereavement and had footage that suggested haunting. Note that I was attempting to rationalise what I was watching knowing nothing other than what the film showed me. Therefore, the film persuaded me that it was at least plausible, and I provided explanations for myself to further this plausibility. This makes Lake Mungo an interesting example of how our minds work in relation to what we see. How much is what we see, and how much is what we want to see? This is a potent parallel for alleged encounters with the supernatural.

Furthermore, Lake Mungo combines talking heads with the images captured by the family to create a genuinely eerie and uncanny atmosphere. It was somewhat like Paranormal Activity but less arrestingly terrifying, yet still scary. It wasn’t until after the film that I checked whether this was an actual documentary, and interestingly the answer made no difference to my response to the film – everything it presented made sense. The ideas expressed were persuasive and the possibilities ambiguous enough to work either way. It is a film that raises fascinating questions about how we view what we see, and what we can keep our eyes out for.

Videodrome

David Cronenberg is a filmmaker who puts a great deal on screen and implies even more. From the ‘plasma pool’ of The Fly to the gangster subculture of Eastern Promises, there is always plenty to consider beyond the copious amounts (often of body parts) that we see. In the case of Videodrome, we see pulsing TVs, organic video cassettes and altered bodies, but there is so much more implied beyond this.

TV channel president Max Renn (James Woods) wants to distribute edgy television, and his quest leads him to Videodrome, a show that ostensibly presents realistic, or even genuine, torture and murder. This raises questions both in the film and beyond it about the public appetite for sex and violence, always major topics for discussion. Notably, the film offers little judgement of this appetite, even Max’s pursuit of Nicki Brand (Debbie Harry) is presented as sleazy and somewhat base rather than perverse or twisted. Nonetheless, the question is raised about the public appetite, something to chew over. From there we see the idea of life being improved by watching television, in stark contrast to moral guardians that might decry our square eyes and corrupted minds. Even when things get really weird, the film feels exploratory rather than condemnatory, pushing an idea to its logical conclusion. As Masha (Lynne Gorman) tells Max, ‘It has a philosophy. And that is what makes it dangerous’. Simply presenting sex and violence is one thing – attaching that material to a philosophy means the material can be believed in, and that is a different matter.

Key to this logical pursuit is Cronenberg’s style, often described as ‘cold’. It’s interesting to consider what this means, as other filmmakers such as Kubrick and Nolan are also described in the same way (strangely, I’ve never heard of a film style described as ‘hot’). Cronenberg’s camera is somewhat detached: the camera observes the changes in Max’s body much as a surgeon might exploratory surgery. And explore we do, as we get up close and personal with the changes in Max’s body.

This brings us to the issue of media effects (thank you, Marshall McLuhan). For decades, studies have argued that media can affect audiences, such as instilling blind acceptance or corrupting morality as already mentioned. There is the counterargument that audiences and media work together to produce meaning and reinforce each other. Videodrome asks what might happen if there were physical media effects, that media caused fiction and reality to blend, including our own bodies to incorporate technology. Answer: it would be gross. But why? If we feel repulsion of the new orifice in Max’s stomach and the merging of his hand with a gun, this likely comes from the plausibility of Rick Baker’s effects. These look and sound like real body parts, unapologetically squishy. The film doesn’t make the body disgusting, but we find it disgusting as if we were actually handling viscera. That’s an impressive feat – producing a reaction from the purely visual and auditory that would also be achieved by the tactile. But what disgusts us is our own bodies. Is that itself not somewhat perverse?

If we consider Max’s new orifice in relation to gender, then he effectively develops a vagina. Is this ‘feminisation’ a corruption of his body? Within aggressively patriarchal western society, feminisation is treated as a terrible nightmare for any man. However, Max is also gaining access to a new form of experience, the feminine, that could be hugely beneficial. What is the ideal body – one that conforms, or one that transgresses? The transgression goes further with the integration of technology as Max inserts videotapes and his gun into his new slit. The ‘new flesh’ could be a higher state of being as the organic and inorganic merge. Technology and humanity coming together is also a full embrace of humanity’s potential, combining the masculine and the feminine. ‘Death to Videodrome’ because that would be purely technological – the new flesh, the way forward, human evolution, is to bring everyone and everything together. With this in mind, Videodrome satirises moral panic over television by suggesting that the effects may be actual, but the result quite different. The ending of the film is deeply ambiguous as to whether Max is destroyed or if he transcends, perhaps because the long life of the new flesh is something Cronenberg leaves to our imagination.

The most remarkable thing about Videodrome is how prescient it proved to be. Replace the various references to the cathode and television with the digital and the computer, and we have a pretty fair description of the mediated and digitised reality of the 21st century. Were the film made today, ‘Digitaldrome’ might well express the same ideas that Cronenberg did in 1983. The smartest horror and science fiction say things about the world that might be. The most unsettling are those that get things right.

Blue Velvet

Blue Velvet is one thing, and also a David Lynch thing. ‘Lynchian’ is so distinctive as to have been included in the Oxford English Dictionary, and in the case of his really weird stuff like Eraserhead and Lost Highway, it is easy to see why. Blue Velvet has a more straightforward and comprehensible narrative than these, yet it is still very Lynchian. The ostensible notion of darkness and malevolence beneath the white picket fences of small-town Americana has been done to death by film noir and neo-noir which turned the city into a visual nightmare and morality into a morass of corruption, as well as more straightforward dramas like Mad Men and Revolutionary Road. And yet, Blue Velvet still possesses a power to shock and unsettle.

Blue Velvet’s plot is a fairly conventional neo-noir: Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle MacLachlan) plays amateur detective after finding a human ear, gets limited help from the police, encounters a virtuous woman in Sandy Williams (Laura Dern) as well as a femme fatale in Dorothy Vallens (Isabella Rossellini), delves into the seedier side of town and runs afoul of the criminal underworld manifested mainly (but not exclusively) in Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper). This narrative would make for a gripping drama in its own right, and such filmmakers as John Dahl, Roman Polanski or Lawrence Kasdan would have made such material their own. In Lynch’s hands, the narrative takes second place to the style, with an almost woozy pace that gives the film a sense of inevitability rather than a more standard deadline narrative.

Lynch’s extreme close-ups are overt and eye-catching, such as his focus on grass and insects as well as the famous slow zoom into a human ear at the start of the film. Slow motion footage is also a Lynch signature, but on this watching of Blue Velvet, what struck me most were the extreme wide angles. Wide-angled shots of streets and rooms give a curious distortion to the image, which does obscure so much flatten objects, cars and figures appearing from a distance and drawing closer yet still somehow distanced.

This effect is most overt when Jeffrey pulls up in his car outside Sandy’s home and school, and also during scenes in weirdly expansive rooms. The most apparent of these are the apartments of Dorothy and also Ben (Dean Stockwell), whose home is both the prison of Dorothy’s husband and child and where Frank brings Jeffrey for a ‘party’. Long shots capture the expanse, with deep focus allowing us to see other figures in the background, but only just – what is with the guy in the background with the bizarre head?!

The wide angles are also evident in the notorious scenes in Dorothy’s apartment where Frank abuses her and also in the final confrontation between Jeffrey and Frank. The wide space makes these potentially claustrophobic scenes expansive, perhaps indicating that the violence and cruelty of Frank is not easily contained. Speaking of expanse, these scenes are also temporally protracted which makes them all the more discomfiting by implicating the viewer for continuing to watch. It is (again) a cliché to talk about voyeurism in this film but there it is, pretty hard to miss, in terms of viewing violence, then engaging with it, and finally practicing it. One can argue that Frank is in all of us, and so is Jeffrey.

The references to ‘a strange world’ sound naïve, surely deliberately so. The world is cruel and venal, figures like Frank and Jeffrey are not as outlandish as we wish they were. Therefore, it isn’t really strange, is it? And yet, come the coda, I find myself wondering if it might have all been a dream? The slow movement of the fire truck and the waving neighbours give this impression, as does as the zoom out of an ear that mirrors the early shot into an ear. This graphic reversal suggests that everything could have been Jeffrey’s dream. Even the final image of Dorothy with her son wearing a spinning-top hat could have been something Jeffrey saw and incorporated into his dream. But Lynch of course keeps this ambiguous, leading me eventually to conclude, maddeningly, that it is indeed a strange world.

Us

Upon a re-watch, you may get more out of a film or identify problems that you missed first time around. Watching Us for the second time, I didn’t pick up thematic elements that I didn’t see previously, but I did appreciate Jordan Peele’s skill as a filmmaker even more than I already did. Peele’s atmospheric build of suspense was all the more palatable as I watched this film in my living room, with all the lights off, of course. Had there been a knock at the door or window, I would certainly have jumped.

Us is an interesting example of a horror movie that falls apart if you think about it. The central premise of an entire ‘race’ of doppelgängers living beneath regular society receives partial and unconvincing explanation; the logistics of the (literal) uprising are implausible; the coincidences are too great. Could any of this happen in reality? Frankly no, and such non-sense is not uncommon in horror cinema – from the conveniently vanishing and regenerating killers of Halloween and Friday the 13th to the monsters of The Babadook and Hereditary, does it all make sense? Often not, and whether or not the horror film works for you depends largely on what you respond to.

In the case of Us, none of the implausibility matters to me, because the skilful filmmaking brings me into the world of the film. The main aspect is the aforementioned atmosphere, created by smart use of shadows and set, Michael Abels’ skin-crawling yet beautiful score, and the performances that are beautifully uncanny. Lupita Nyong’o rightly received acclaim for her dual performances as Adelaide and Red, but the other actors are also impressive, as they must embody both ‘civilised’ people and the animalistic qualities of the Tethered. Movement is key to this, such as Winston Duke’s confident swagger as Gabe but lumbering and almost bearlike gait as Abraham, while Evan Alex’s timid small boy motions as Jason contrast sharply with his scuttling as Pluto. Returning to Nyong’o, the movements of Red are simultaneously stiff and fluid, as though a stalagmite shifted from one point to another. This raises the aspect of dance in the film, a key parallel between Red and Adelaide that also spills into the editing, images pirouetting from one to the other with an elegance both eerie and ethereal.

As for the allegory, how well does it work? On the one hand, it is a rather heavy-handed version of an underclass uprising, perhaps one that Karl Marx would applaud. Wealth and class are targeted throughout, often in amusingly satirical ways such as the darkly humorous use of ‘Fuck the Police’. But does Us commit to its central premise in its final loyalties? We see the Wilson family triumph over their doppelgängers, killing all of them in satisfyingly visceral ways. Granted, there is a twist which you may see coming, but either way the work of the doppelgängers is done, as the film’s final image offering an ambiguous image of unity and disruption. Is this a brave new world for us/the US? Maybe there could be a sequel, Us V Them, but we hardly need it. If you accept its central premise and the atmosphere envelops you, Us remains a chilling and unsettling portrayal of class relations turned asunder.