Home » Posts tagged 'halloween'

Tag Archives: halloween

HorrOctober Wrap Up

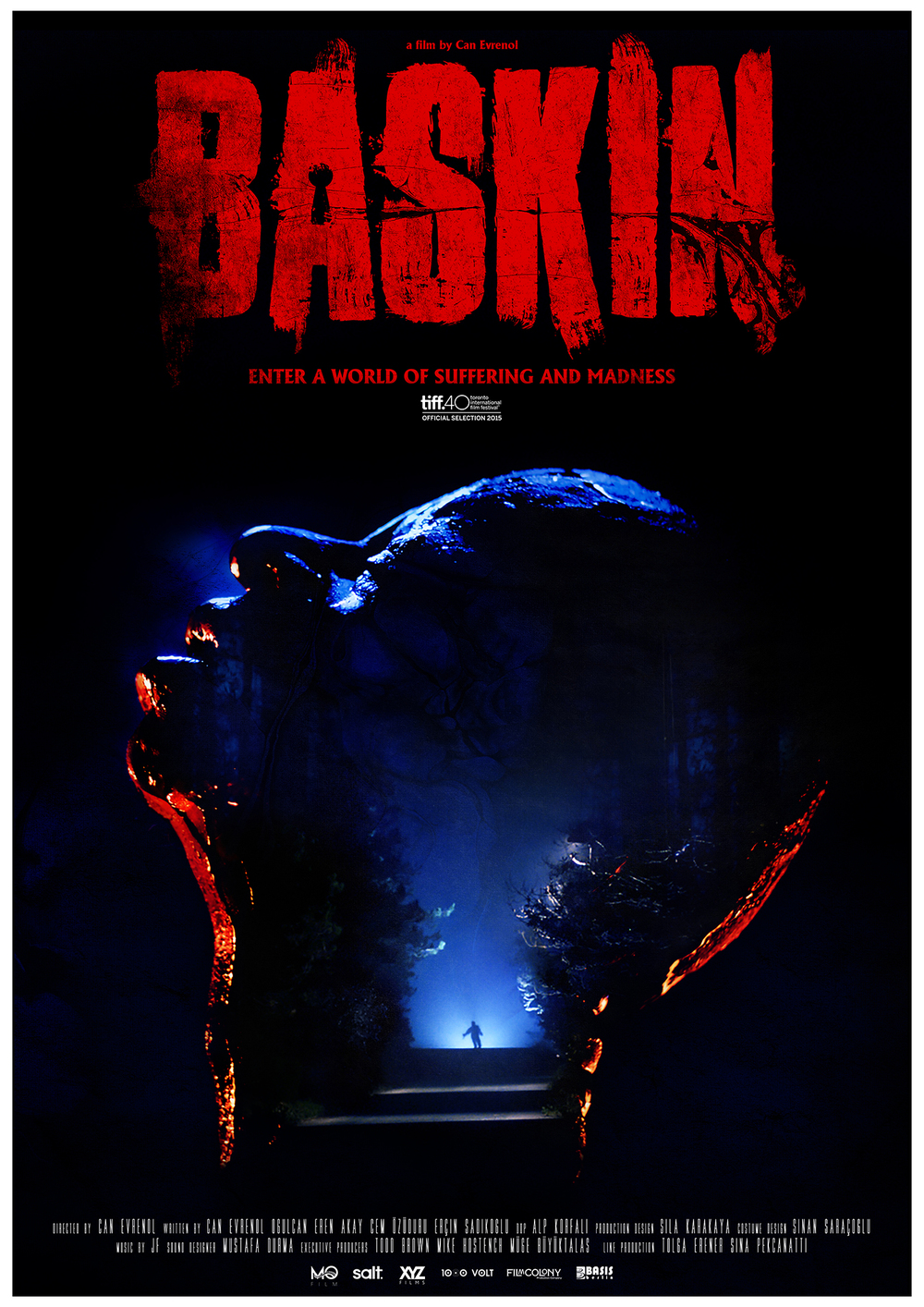

To conclude HorrOctober, I watched three different horror films in quick succession. Baskin on 30th October, and then a double bill of 2018’s Halloween as well as the first Final Destination (ho ho) on 31st October. Baskin I knew nothing about, and quickly learned that it is Turkish, beautifully designed and thoroughly freaky. From eerie dreams to a dread-drenched location to graphic gore (including serious eye trauma) and a doom-laden finale, this blend of haunting, occult and body horror left me shaken and stirred. Writer-director Can Evrenol focuses on a squad of police officers investigating a disturbance rather than teenagers who stumble into something, and this gives the film a convincing flavour. The five cops are clearly out of their depth and there were a few points when I was almost yelling ‘Run, you fucking idiots!’ However, their training, authority and, let’s face it, guns did indicates why they believe they can handle themselves. By the time they ascertain that they cannot, it’s rather late. Interwoven with the deranged and gruesome material, the film has a strong element of melancholy, which gives it a human heart that makes the fear all the deeper. As it isn’t that well known, I won’t say more about Baskin except that it is highly recommended.

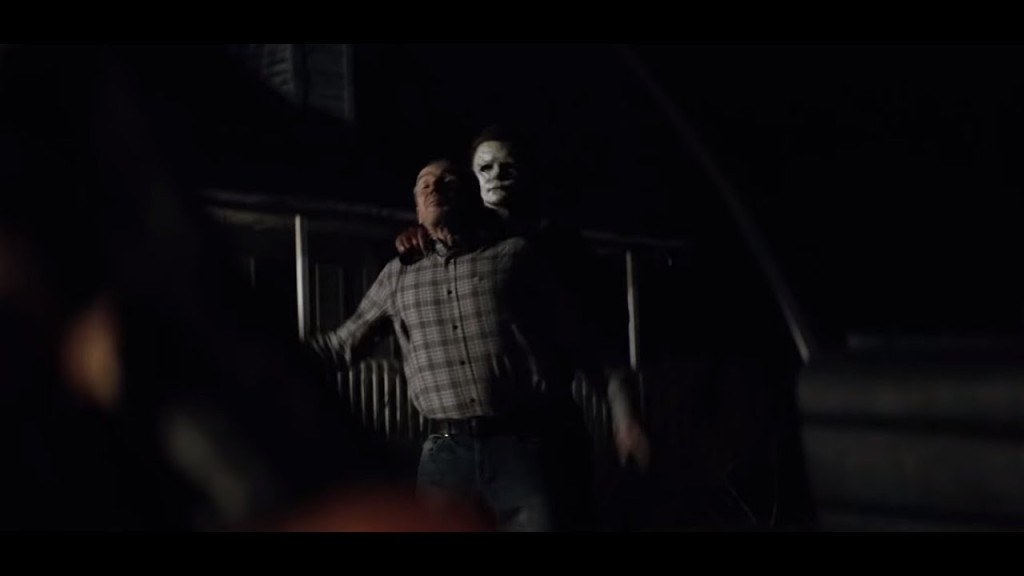

I viewed and reviewed David Gordon Green’s Halloween when it came out in 2018, and as well as enjoying the film as a horror I was also impressed with its progressive gender politics. It was interesting to watch this film again soon after re-watching the 1978 original. The two films feature a similar creeping dread, judicious use of music and long takes that escalate the tension. The 2018 film is less stripped down than the original and its higher budget helps to make it much slicker. It also has some distracting comedy elements, and is at times over-stylised, but it does succeed in making Michael Myers frightening. This is partly due to Michael being an unknowable evil, the looming shape that appears and kills without warning or hesitation, just as he was in John Carpenter’s film. But it is also due to the added visceral gore of this film. Several points show bodies that have been violently broken, and this makes the danger of Michael somewhat more tactile and nasty.

Final film of the month was the much-vaunted Final Destination. I found this to be an amusingly convoluted take on a simple idea, that of Death being the killer that stalks the (incredibly 90s) group of teenagers. The film is crammed with devilish designs such as a sword in stained glass that a victim bends down in front of, as well as the Mousetrap style ‘accidents’ that occur. These elements made for an effective blend of suspense followed by gory release.

My main criticism of Final Destination is that it was somewhat over-cranked. The regular device of having a dark shadow or cloud appear behind the victims, as well as the seemingly sentient movement of liquid, made the idea of a design behind what was going on too explicit, rather than suggested. In addition, random electricity was a danger used too frequently, even though no victim was actually electrocuted. Had the deadly events occurred with a greater sense of randomness, I think it might have been scarier, suggesting that our heroes’ attempts to find meaning in these incidents might have all been in their heads. After all, what is more frightening than the random and ultimately indifferent nature of death? Then again, without that element we wouldn’t have had Tony Todd’s delicious monologue about mortality. The moral of the story, it would seem, is always listen to Candyman.

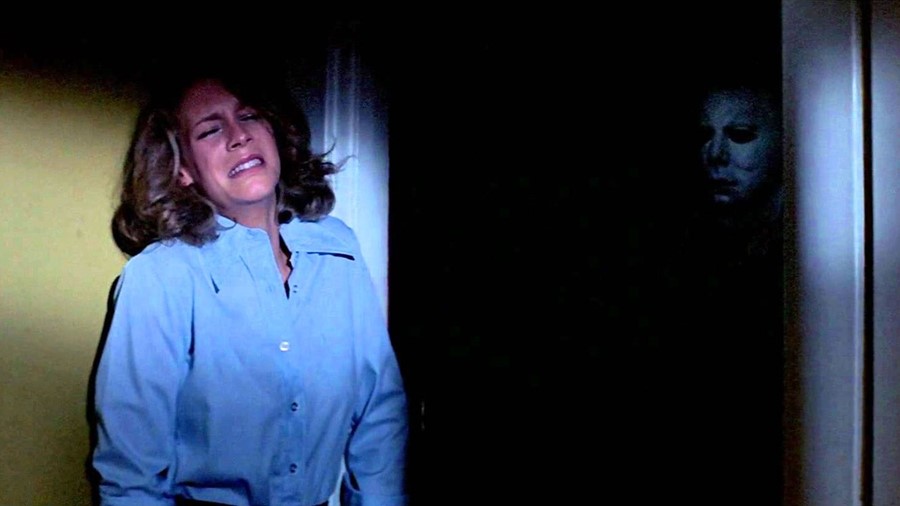

John Carpenter’s Halloween

More than forty years since its release, John Carpenter’s Halloween still has the power to unnerve. For all the imitators, sequels and remakes that have come in its wake, the raw, primal power of the 1978 original is undiminished. From the arresting opening to the atmosphere of the middle section and the rising terror of the final act, Halloween is a textbook exercise in suspense, dread and shocks. Yes, one can object to Michael Myers’ ability to move very quickly at some moments and very slowly at others, but this adds to the uncanny quality of the Shape (Nick Castle), making him a threat both human and yet something Other.

Carpenter’s greatest tool is simplicity. Narratively, we follow a killer who escapes from incarceration, selects, stalks and strikes his targets; our heroine Laurie (Jamie Lee Curtis) goes about her normal life then responds to the sudden threat; Dr Loomis (Donald Pleasance) provides the background. The events of the narrative are brief, aside from the opening 1963 sequence the story covers barely 24 hours. And in stark contrast to most slashers, the body count is low. Only five people are killed over the course of the film, and each death carries weight. Far from being a group of anonymous teens, we see pain, injury and gain a sense of Michael’s sadism, especially in perhaps the film’s most distressing moment as he strangles Lynda (P. J. Soles) with a telephone cord.

Stylistically, Carpenter makes great use of long takes and wide angles, which raise suspense by compelling the viewer to look for the threat within the wide frame, and we also wait for something to happen as the prolonged take continues. Not only does this increase our sense of fear, but the film also implicates the viewer in the violence – we are waiting for something to happen and thus complicit in Michael’s murders. This point is emphasised in the extended point-of-view shot in the opening sequence, while the reverse angle makes the universality of violence all the more apparent. We think of ourselves as good people, but if a little child can viciously stab their sibling to death, what might any of us be capable of? The film continues this conceit by showing evil’s ubiquity – Michael escapes from the asylum and returns to his family home, but while the people of Haddonfield fear the Myers house it is notable that Michael only stops there briefly. Most of the violence takes place in the homes where Laurie and Annie (Nancy Loomis) babysit, both of which are plunged into shadow where Michael lurks and then emerges with cruel intent. Though in the final moments Michael is literally cast out, the final montage presents various domestic spaces that Michael previously occupied, expressing the potential for evil to occupy any area that we might regard as safe.

Us

Jordan Peele begins his new film with a long take of a rabbit. Slowly the camera pulls back, revealing many more rabbits. As the camera’s scope widens further, what appears to be a school classroom steadily appears. Nothing overtly horrific happens in this title sequence, yet it is deeply unsettling and disturbing. This sequence is testament to the power of the long take, a stylistic feature common in horror cinema from Halloween and The Shining to It Follows and Hereditary. The long take generates discomfort as the viewer yearns for a cut that could break the tension. In the case of Us, there is little sense of release, as the tension builds even as the film cuts between past – a childhood trauma of Adelaide (Madison Curry) and present – the adult Adelaide (Lupita Nyong’o) on her present-day vacation with husband Gabe (Winston Duke) and children Zora (Shahadi Wright Joseph) and Jason (Evan Alex). The slow burn menace includes a pattern of coincidences, home invasion and confrontation with the uncanny, that which is both familiar and unfamiliar. The tension is punctuated by jump scares, brutal violence and dark humour. Nyong’o is electrifying, delivering two distinct and equally compelling performances. The rest of the performances are very strong, especially as each actor must play two roles: one a civilised human and the other animalistic. When the violence happens, it is sadistic and merciless, as the line between civilized and uncivilized becomes increasingly blurred.

Despite this blurring, Peele never blunts his razor sharp satirical edge. Us is that finest type of horror cinema: steeped in the tropes and techniques of the genre, while using these features for incisive social commentary. Playing on ideas of class much as Get Out played on race, Us is a nightmare version of Karl Marx’s proletariat uprising. Socio-economic structures are targeted as affluence and privilege are attacked. The thematic and narrative doubling is replicated by the film grammar, as images are intercut with spine-tingling precision. The film is an elegant, demonic dance of micro and macro scales, interspersing the real world and allegory, past and present, identities and faces.

Halloween

John Carpenter’s Halloween, to give the 1978 film its full title, has an extraordinary legacy. On its release it became the most commercially successful independent film of all time; it helped solidify the elements of the slasher sub-genre that became a staple of 80s cinema, a rite of passage for many a filmgoer and a ripe area for critical study. John Carpenter’s Halloween also spawned a franchise that has continued for forty years, through multiple sequels and remakes. Any new addition to the Halloween lineage, therefore, must strike a balance between acknowledging this legacy and declaring its own identity. David Gordon Green’s Halloween achieves this balance by narratively ignoring every film in the franchise since 1978. This frees Green and his co-writers Jeff Fradley and Danny McBride from worrying about consistency, which is a relief because Michael Myers and Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis) have been through so many transfigurations that consistency died a grisly death long ago. The new film can therefore focus on its own identity, closely tied to the iconic figures of the series. The latter is as implacable, relentless and silent as ever, as performers James Jude Courtney and Nick Castle convey the unknowable evil that Michael has always represented. It is perhaps a heavy-handed device that the viewer never sees Michael’s face, and the only sounds that we hear from him are heavy breathing, but this does not detract from the imposing Shape that lurks in the frame, his iconic white mask now battered and dirty but still unmistakably menacing. Green stages several set pieces that convey a palatable sense of fear. In one bravura sequence, captured in a single take, Michael enters the frame in the foreground and watches a woman through a window, his reflection in the glass standing in for that of the viewer. Then he moves out of shot, only to reappear in the background while the woman inside the house continues oblivious. The climax of the sequence echoes the beginning and is genuinely shocking, despite being clearly telegraphed. Other set pieces also emphasise Michael’s power and brutality, but the film’s master stroke is its presentation of Laurie. Curtis is fresh and exciting, a sympathetic embodiment of dealing with trauma. Halloween’s willingness to engage with PTSD from a female perspective is a development of the genre’s long-established trope of the Final Girl, as three generations of the Strode family – including Laurie’s daughter Karen (Judy Greer) and granddaughter Allyson (Andi Matichak) – reclaim a narrative too long held by men. Whereas the original Halloween and so many slashers since (not to mention other genres and a little thing called the real world) emphasise male subjugation of women, Halloween 2018 shows female wisdom, ingenuity, compassion and the determination to take control. It might have been even more progressive were the film been written and directed by women, but by committing to this female assertion, Green shows that challenges to patriarchy and its damaging affects, neatly represented by Michael Myers and his ilk, are the responsibility of everyone that wants monstrosity to be contained and curtailed.

Get Out

Imagine if Ben Stiller had encountered hypnotism and brain surgery when he went to Meet The Parents. That is a fair description of Jordan Peele’s Get Out, a gripping, thrilling and at times shocking horror film about social attitudes and the power of privilege. Writer-director Peele structures the film carefully, as an opening sequence is conducted almost entirely in a wide angled, single long take, that echoes Halloween and the more recent It Follows. Such composition sets the scene of menace and danger as part of the overall picture if not seen immediately. The viewer is then introduced to likeable couple Chris Washington (David Kaluuya) and Rose Armitage (Allison Williams), taking a weekend trip to Rose’s parents Dean (Bradley Whitford, whose character echoes his from The Cabin in the Woods) and Missy (Catherine Keener, turning her usual comforting presence to more sinister ends). Chris is concerned about the Armitages’ attitude towards his race, but despite Rose’s assurances a sense of unease rapidly develops as the family sees too clean cut and their African-American servants are clearly strange. As other guests arrive for a party their racial attitudes shift from initially grating to increasingly creepy. Past traumas and emotional vulnerability are exploited as things become ever more sinister, with scenes of direct mental manipulation proving especially unnerving. In its final act the film moves away from psychological scares to more physical ones, becoming increasingly hysterical and ultimately less effective. Although a potentially devastating plot twist is avoided, Get Out contains more than enough atmosphere and dread to leave one feeling shaken and disturbed.

Freshness and Familiarity Part Two – Repackaging Star Trek

SPOILER WARNING

Star Trek Into Darkness (J. J. Abrams, 2013) constitutes a variation in the practice of re-launching previous texts and franchises. Whereas Star Trek (Abrams, 2009) was a re-launch of the Star Trek franchise as a whole, Star Trek Into Darkness combines features of both the sequel and the remake (Semake? Requel?), that repackages elements from previous Trek instalments into a new form that is influenced by its 21st century production context. STID’s narrative follows on from Star Trek, developing the relationships between Kirk (Chris Pine), Spock (Zachary Quinto), Uhura (Zoe Saldana) etc., and also expands the universe established in Star Trek, especially the aftermath of the attacks of Captain Nero (Eric Bana) and the destruction of Vulcan, as well as the Federation’s uneasy relationship with the Klingon Empire. But STID also remakes Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (Nicholas Meyer, 1982), updating it with 21st century sensibilities and re-interpreting the mythos around Khan (Benedict Cumberbatch). This repackaging creates particular tensions within the film text, leading to frustrations for viewers and interesting areas for consideration.

Henry Jenkins and Billy Proctor give in-depth (and very funny) critiques of the film, and Rob Bricken writes highly inventive criticisms of STID’s relationship with Star Trek in general and with TWOK (two can play that game) in particular. These writers demonstrate both dissatisfaction with the film on its own terms, and its perceived besmirching of a treasured text. I consider myself a dedicated Trekker, but TWOK never seemed that great to me, which might explain why I was less bothered with the earlier film being referenced in STID. Let us not forget that referencing or remaking or even contradicting an earlier text need not impinge upon the integrity of the original or one’s enjoyment of it. TWOK stands on its own whether you consider STID or not, much like the originals of Halloween, A Nightmare on Elm Street, The Hills Have Eyes, Friday the 13th, Psycho, Ocean’s Eleven, Get Carter, Alfie, The Italian Job, Ringu and other films that have been remade (there are a lot). Even if the remake is terrible, it need not tarnish your enjoyment of the original. I have never understood the obsession with the original, that which must not be distorted or besmirched because it constitutes some form of sacrilege. The responses to STID have been thankfully moderate, at least in comparison to Star Wars fans who protest that their childhood was somehow raped by Yoda’s pinball act in Attack of the Clones (George Lucas, 2002). They’re just films, people.

Sorry, got side-tracked there. There is much to criticise in STID. The shot of Carol Marcus (Alice Eve) in her underwear is gratuitous and annoying (no, I will NOT stick a picture of it on here). Many of the plot conveniences and gaps in logic are nonsensical, such as the Enterprise being hidden underwater to avoid being seen by the local inhabitants. Would it not have been better hidden in planetary orbit? In addition, the naivety of Starfleet in relation to “John Harrison” is rather striking. Harrison is perfectly placed to take advantage of Starfleet protocol in order to attack its command elite, yet no one thinks of this vulnerability until Kirk does just at the most dramatic moment in order to demonstrate that he is ahead of the curve. Later, the Enterprise as well as the dreadnought vessel Vengeance are heavily damaged and fall into Earth’s atmosphere, despite not having actually been in orbit. I don’t expect scientific accuracy, but would it have killed them to have the ships actually fighting in orbit?

The falling-out-of-orbit leads to the biggest absurdity of the whole film, which is that the correct process for warp core realignment is well-placed kicks. That’s right, an enormously powerful, dangerous, already damaged and unstable nuclear reactor is put back into working order with repeated, well-placed kicks. Maybe they should have tried that at Chernobyl. While Spock had to perform a similar task in TWOK, he had to rearrange some handheld objects in a delicate operation. (Actually, both instances of radiation contradict general Star Trek science – the warp core is run by matter-antimatter infusion, not nuclear power, so there should be no radiation anyway. It can be unstable, breach and cause a massive explosion, as seen in Star Trek: Generations [David Carson, 1994], but radiation is a pure plot convenience to allow agonising sacrifice.) STID’s intercutting between Kirk kicking the core and the ship spiralling through the clouds is very dramatic, but if you stop to think about it, it’s actually very silly.

The warp core sequence demonstrates both the strength and weakness of Abrams’ directorial approach. His aesthetic is highly dynamic, with extensive use of mobile, handheld camera with a slight wobble, and the ubiquitous lens flare that he is seemingly in love with. The screenplay by Roberto Orci, Alex Kurtzman and Damon Lindelof may have holes you could fly the Enterprise through, but with the plot whipping by at warp speed it is easy to miss these gaps in logic. But is this not rather patronising on the part of the filmmakers? The implication is “Don’t worry about the plot, kids, just look at the shiny-shiny while we shoot through space and everything is so coooooooool!” STID is certainly entertaining, but the care and precision of Gene Roddenberry and especially Ronald D. Moore, Michael Piller and Ira Steven Behr is missing. This is a difference between television and film – the contained narrative of a movie frequently does not have the space to develop fictional worlds and their infrastructure. When Star Trek movies have inconsistencies, like everyone in Generations forgetting that the warp core could be ejected, they are only apparent to dedicated Trekkers. With Abrams’ films, I don’t start questioning the gaps in logic until afterwards, because I am enjoying the film too much to care. When I do think about it, it is rather patronising, but not so much that it makes me die a little inside. The previous Star Trek movies have a more coherent internal logic, but they are a rather more sedate.

Not that they lack in action (despite the derogatory term, Star Trek: The [Slow] Motion Picture [Robert Wise, 1979]). Several of the earlier films feature spectacular space battles, including The Undiscovered Country (Nicholas Meyer, 1992), First Contact (Jonathan Frakes, 1996), Nemesis (Stuart Baird, 2002) and The Wrath of Khan, just one of several elements of that earlier film that are repackaged in this latest offering. In TWOK, the badly damaged Enterprise battles another Starfleet vessel, the Reliant, commandeered by Khan; in STID, the badly damaged Enterprise battles another Starfleet vessel, the Vengeance, first under the command of Admiral Marcus (Peter Weller) and then commandeered by Khan (notice a pattern emerging?). Cunning and guile are the key weapons used to achieve victory in both cases, although STID features more lens flare.

A strength of Abrams’ warp speed approach to visual storytelling, however, is that it does allow for moments of world-building that previous Star Trek films neglected, as the vast majority of action in earlier films is confined to the Enterprise. First Contact and The Voyage Home (Leonard Nimoy, 1986) largely take place on Earth, but these are both time travel narratives and do not feature the infrastructure of Starfleet or Earth in the 23rd or 24th centuries. Abrams’ version spends more time on Earth, indeed in interviews Abrams mentioned that after making Star Trek, he wanted to spend time in the cities. Star Trek and Star Trek Into Darkness depict Earth in the 23rd century, the utopia of Roddenberry’s vision as there is no indication of poverty, class or even capitalism (although commerce is neatly avoided). But there is still trouble in paradise, as some diseases cannot be cured except by Khan’s super-blood, and men like Admiral Marcus still possess defensive mentality.

This mentality manifests as the covert organisation Section 31, an entity that appeared in several episodes of Deep Space Nine. This unsavoury agency of the Federation was responsible for very questionable activities during the Dominion War story arc of DS9, in which the agency was described as having existed since the birth of the Federation (it also features in a number of Star Trek novels). Its presence in STID is a demonstration of a less-than-perfect future, and a further element in the repackaging of Star Trek. Another element is Khan’s age of over 300 which would place his birth in the late 20th century. In his original incarnation, Khan Noonien Singh (Ricardo Montalban) led a revolt against humanity in the 1990s, the revolutionaries sentenced to cryogenic exile in deep space. I didn’t notice Eugenics Wars in the 1990s, so the mention of this piece of 1960s future history is anachronistic to the 21st century viewer. But its inclusion demonstrates fidelity to the original, the wibbly-wobbly, timey-wimey relationship between Star Trek á la Roddenberry and Star Trek á la Abrams. Proctor comments that Star Trek 2009 was not technically a reboot, since its narrative connects to that of the original Star Trek, rather than working as a completely independent narrative like Batman Begins (Christopher Nolan, 2005), Casino Royale (Martin Campbell, 2006) or The Amazing Spider-Man (Marc Webb, 2012). Khan’s history is a further demonstration that this narrative is not separate from previous Trek, and that STID’s repackaging is a hybrid of sequel and remake. Much as Spock Prime (Leonard Nimoy) told Kirk that he and Spock are destined to have a great friendship, it also seems that Kirk and Khan are destined to clash.

Casting Khan as a wronged terrorist, rather than a revenge-crazed despot, articulates STID in a post-9/11 framework. Admiral Marcus justifies his militarisation of Starfleet as a response to the terrorist attack of Nero – Earth needs to be prepared against future attacks and the looming threat of war with the Klingons. You might therefore expect Marcus to be a little more paranoid about the 20th century superman he has been blackmailing, but again, only in so far as it serves the plot. Marcus resorts to extreme measures after Khan’s attack, sending Kirk and the Enterprise off to kill Khan before arriving in the Vengeance to kill them as well, but maybe he should have kept Khan on a tighter leash to begin with. But as Hitchcock said, then there wouldn’t be a film.

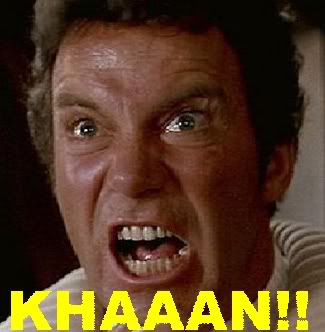

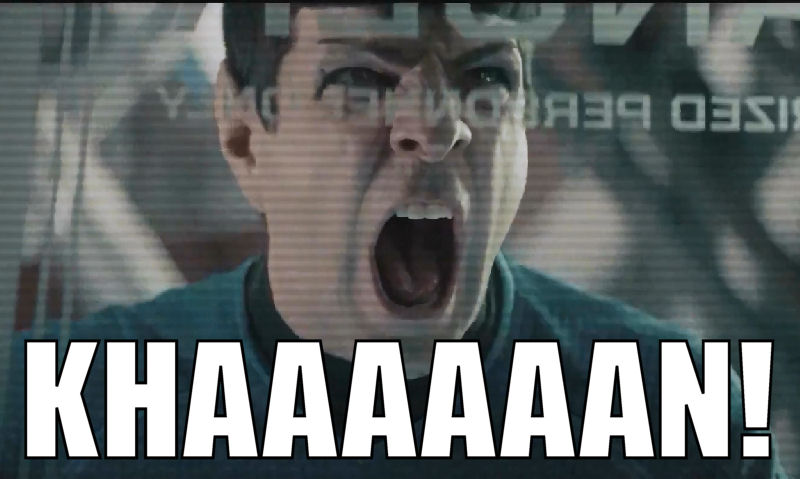

Marcus and Khan’s relationship though does create a further dimension which TWOK lacked – making Khan sympathetic. Ricardo Montalban’s Khan is crazed for revenge – the tagline informs the viewer of what to expect: “At the end of the universe lies the beginning of vengeance” (the name of Marcus’ dreadnought may be a further inter-textual reference). But Benedict Cumberbatch’s Khan has been coerced into developing new weapons and defence systems. Placing Khan under duress makes him more sympathetic and interesting; his main motivation is to protect his people and at one point he and Kirk form an alliance against their common enemy Marcus. This was one of the most satisfying elements of STID for me – take the original clash between Khan and Kirk and turn it around. It made Khan (perhaps ironically) more human, especially as the key to defeating him was his compassion for his own people. Some elements of TWOK were repackaged less successfully, such as the death of Kirk and Spock’s anguished roar:

It may be emotionally powerful, but perhaps it is an inter-textual step too far.

The treatment of Khan encapsulates the repackaging of TWOK that STID performs. STID repackages the iconic moments of TWOK with a different emphasis. This emphasis comes from the film’s concern with terrorism and violence, the Darkness that is Trekked into. Adam Ericksen discusses this in a fascinating reading of the film as the antidote to terror, rather than the War on Terror (which is apparently over). Kirk is initially committed to finding Khan and avenging the death of Captain Christopher Pike (Bruce Greenwood), but contravenes Marcus’ direct order (Jim Kirk, insubordinate? Shocking!) and takes Khan into custody, after punching him ineffectually a few times (violence solves nothing). Spock is consumed by grief and rage over the death of Kirk and attempts to kill Khan, but crucially Khan must live so that Kirk can be resurrected (sparing us Star Trek: The Search for Kirk). Marcus’ journey was into darkness because he saw violence and militarism as the solution to threats like that of Nero and the anticipated war with the Klingons, and he exploited Khan in serve this end. Khan’s journey into darkness is motivated by a massive superiority complex and fuelled by anger and, initially, Kirk and Spock both seek retribution. But crucially, when both of them could kill Khan, they do not, because killing is never the answer. STID may journey into darkness, but there is light at the end of the torpedo tube.

Through its engagement with violence and retaliation, STID repackages the features of TWOK in relation to its 21st century context. Much of Star Trek’s ideology, such as the platitudes espoused by Captain Picard in First Contact, can seem naïve in an era of violent clashes all over the world. Earlier decades were not necessarily more peaceful, but we had not seen planes fly into buildings back then, a contemporary trauma echoed in STID when Khan pilots the Vengeance’s death plunge into San Francisco. Furthermore, we did not have hatemongering assailing us from every other website, even if it is satirical. STID demonstrates that even in today’s cynical and embittered times, there is still a place for Gene Roddenberry’s optimistic vision of the future. Kirk and Spock both turn away from violent revenge, and Kirk’s speech at the end of the film emphasises the importance of and need to turn away from violence. For it is when we put aside violence, and encourage life instead of death, that we can truly go where no one has gone before.

Frightful Five No. 2. “The Silence of the Lambs” (Jonathan Demme, 1991) [SPOILER WARNING]

I rate this as one of my favourite films ever, although it is not quite the scariest. I have also seen it many times and performed some detailed analysis of the narrative, mise-en-scene, cinematography and editing. This much analysis could lessen its impact, but The Silence of the Lambs never fails to draw me in, particularly in its most chilling moments. Both Dr. Hannibal Lecter (Anthony Hopkins) and Jame Gumb/Buffalo Bill (Ted Levine) are terrifying creations that could so easily have been crass and lurid, but director Jonathan Demme uses a strikingly sparse approach, both narratively and stylistically. This sparseness has the effect of focusing the viewer’s attention on the events unfolding, and the focus exacerbates the fear.

Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster) provides a viewer’s surrogate. For much of the film we are aligned with her, learning more about Buffalo Bill through her conversations with Dr. Lecter as well as autopsies and other parts of her investigation. Jodie Foster has been rightly praised as giving one of the great screen performances, and on my first viewing I was struck by the film being very much about her. Not only do we experience her intellectual investigation, but her compassion, discomfort and eventual fear are all beautifully expressed, both by Foster’s performance and Demme’s direction. A particular technique used is subjective camera angles, with conversations shot face-on rather than a more typical over-the-shoulder shot. When Starling and Dr. Lecter converse, the shot/reverse-shot pattern fills the frame with their faces, which is especially unnerving when Dr. Lecter is staring out at you. Anthony Hopkins uses a simple technique of not blinking, making his stare all the more unsettling.

Hopkins is sometimes criticised for being something of a ham, and in Hannibal (Ridley Scott, 2001) and (to a lesser extent) Red Dragon (Brett Ratner, 2002) there are grounds for that. But in The Silence of the Lambs he is perfectly restrained, as part of Demme’s sparse approach. Impressions often misrepresent the famous “FFFFFF” over the census taker’s liver, hamming it up beyond what Hopkins does. Like the film as a whole, his performance is tightly wound and precisely focused.

The film’s precision and sparseness make the moments of violence all the more shocking and frightening. Dr. Lecter’s escape from his elaborate cage is ghastly in its unrestrained savagery, and the baroque display he leaves behind expresses the monstrous intelligence behind such brutality. But his most frightening moments are psychological, his psyche boring into Starling’s to expose her vulnerabilities and leave her open to a disturbingly invasive interrogation.

Invasion is a key theme throughout The Silence of the Lambs. Gumb’s attempt to transform into a female is an invasion of his own identity and, more disturbingly, that of his victims. The women slain and skinned by Gumb not only have their bodies invaded, but their minds as well with the psychological torture inflicted in his well, demonstrated through the suffering of Catherine Martin (Brooke Smith). Furthermore, Gumb invades their very identity by appropriating them for his own purposes. In her meetings with Dr. Lecter, Starling’s mind is invaded as he identifies her concerns and forces her to confront her central fear, manifested by the screaming of the lambs. In conversations, I have heard criticisms of Starling’s central fear, questioning the credibility of such an event being so traumatic. To me, it does not matter whether I or anyone else would find a particular event upsetting or traumatising – this is Starling’s fear and it matters to her, and I have always found her sufficiently engaging to accept her position. The point is not what her trauma is, but that she has one, which Dr. Lecter identifies and forces her to confront. Call it fear therapy.

The invasions work on a wider scale as well, as the genre of The Silence of the Lambs is a source for debate. Narratively, it is a detective thriller, but a detective story invaded by tropes and elements of horror. Horror moments abound: the storage unit Starling explores; the Gothic-esque halls of the Smithsonian where she meets the etymologists; the death’s head moth itself. The climactic sequence in Gumb’s cellar is both an invasion of his space by Starling, and an invasion into her security as she is viewed through Gumb’s night vision goggles. Starling’s final victory over Gumb breaks the window of his cellar, allowing sunlight to invade this dark recess, but the bright, sunlit places are themselves invaded, as the final scene features Dr. Lecter at an island resort, watching Dr. Chilton (Anthony Heald) whom, he indicates, will shortly be on the menu. Buffalo Bill is disposed of, but there are still monsters out there, stalking.

A key component of horror cinema is cruelty, the continued depiction of people being hurt or persecuted. Action cinema focuses on the hero fighting back and demonstrating their ability to take control of their situation. Horror continues the subjugation, cruelly prolonging the plight of its characters. Even when Starling should have Gumb cornered, the film’s cruelty continues as we watch her plight in POV shots from Gumb’s perspective. Horror cinema compels us to watch the disturbing and horrific events through long takes, static camera and subjective shots. If we are to maintain our engagement in the film, we must continue to endure this cruelty. The end credits of The Silence of the Lambs perpetuates the film’s cruelty by not fading to black as a long take continues over the street, people walking about their daily lives, with Dr. Lecter having disappeared into the distance. We want him to reappear, perhaps even to be caught, but the film tantalises us with this possibility, perhaps inducing us to check the front door is locked.

I first saw The Silence of the Lambs on a very small TV, with a single speaker, in black and white. Despite the basic viewing conditions, I was utterly hooked and thoroughly petrified. I have subsequently seen it many times, on DVD and in colour, on a much larger TV, and it still grips and chills me in equal measure. Other Thomas Harris adaptations have varied in quality – Hannibal is operatic but rather silly; Red Dragon is taught but fairly ordinary (I am yet to see or read Hannibal Rising [Peter Webber, 2007]). Before all of these came Manhunter (Michael Mann, 1986), which I have a close relationship with. Manhunter is a fascinating film, operating on a number of stylistic, narratological, psychological and philosophical levels. It is striking, compelling and at times disturbing, but I would not call it frightening. The Silence of the Lambs, however, remains both shocking and disturbing in equal measure, and one of the scariest films I have seen. Not quite the scariest though.

Frightful Five No 4. “Jaws” (Steven Spielberg, 1975)

I avoided seeing this for the longest time, not out of fear, but because of the damaging representation of sharks. Then I remembered that Jaws is a film, I know it is a fiction and I will not be turned against sharks by it. Furthermore, me not seeing it makes no difference to anyone else’s opinion, so I did. It was a very specific occasion – 30th December 2000, alone in my university room. I ordered pizza, drank Smirnoff Ice (I think) and enjoyed Spielberg’s mastery of suspense and the cinematic medium.

Spielberg is, for my money, the most accomplished director working in Hollywood, if not the world, today. Several of his films are regarded as masterpieces, such as Close Encounters of the Third Kind, E.T.: The Extra Terrestrial, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Schindler’s List and, of course, Jaws. Specifically, Jaws is a masterpiece of suspense (also used to great effect in Jurassic Park and War of the Worlds), and despite having watched it multiple times, I always find my pulse quickening practically at the same tempo as John Williams’ score. Certain scenes are especially tense: the two fishermen who get yanked into the sea and are “chased” by a large piece of driftwood; the opening attack on the swimming girl; the attack on a small boy. Best of all is the night dive, when Hooper inspects a ruined boat underwater and finds a large tooth. As he inspects the tooth, the music playing, the viewer expects the shark to attack, but instead a decapitated head appears out of the hole in the boat. I screamed the first time I saw that, and I still scream (perhaps deliberately) in subsequent viewings, even though I know it’s coming.

The fact that my pulse accelerates and I jump and scream, even when I know what is coming, is testament to Jaws’ power. Once again, the threatening environment is as important in generating fear as the threatening presence. But whereas in Paranormal Activity the environment is mundane, in Jaws it is an alien and menacing world that can easily kill us. Most will agree that the shark itself look pretty fake and hardly menacing, but it pales in comparison to the vast, hungry, uncaring sea. Martin Brody’s (Roy Scheider) fear of drowning makes him our substitute, and the knowledge that, regardless of anything else, it is never completely safe to go into the water. The film epitomises an intractable adversary through the figure of the shark, presented not so much as an animal as a manifestation of the engulfing sea. This is a common use of animals as enemies in films – from the lions in The Ghost and the Darkness to the wolves in The Grey, animals do not express their real-world counterparts, but our fear of the wild, the unknown world beyond our own. The sea is perhaps the best example of this great unknown – an indifferent and all-consuming expanse. Jaws expresses this fear through its use of suspense and by playing upon our expectations, making it a consistently and repeatedly nerve-wracking experience.

Halloween and the Frightful Five

In keeping with the trend at Halloween, the next five days shall feature a series of posts detailing my top five scariest movies, why, how I understand horror and fear in films in general, and what makes these films scary for me. I am sure many will read these and say “That’s not scary!” and “What about film X or Y?” Please tell me how wrong I am, I love debate.

Horror is one of the hardest “genres” to classify, and I doubt I will offer anything definitive here. I think the reason it is so hard to define is that what frightens us varies hugely. The Exorcist is often described as the scariest movie of all time (Entertainment Weekly, Movies.com), and by at least one reknowned critic, the greatest film of all time; it could also been described as over the top and rather silly. A friend of mine is a huge horror fan and a respected horror expert, and he jumped repeatedly at The Cabin in the Woods; I laughed (that is not a criticism). I am very specifically discussing what films scare me the most, in terms of what I consider to be horror tropes and features (so such “real world” scares as Children of Men, United 93 or The Dark Knight will not be discussed here).

I was a very sensitive child so avoided horror like the plague until I was nearly twenty – reading the Penguin version of Dracula freaked me out for weeks, and when the Grand High Witch appeared in the film adaptation of The Witches I left the room. As a child of the 80s, I was the demographic the Daily Mail was “concerned” about being vulnerable to Video Nasties such as The Evil Dead and Driller Killer, but I was too much of a coward to even consider watching such things. I knew kids at school who jabbered about Freddy Krueger being much scarier than Dracula because he had knives for fingers (obviously), and I thought they were too young to see such things. Later on, I learned that there is a certain kind of pleasure in being frightened, in the safe way that horror movies provide. I think many would agree that the appeal of a horror movie is that we can be scared, but not actually hurt or placed in danger. There are of course exceptions – heart attacks at screenings of Jaws, vomiting at Alien and running out of The Exorcist and into a church.

Over the years, I’ve had scary experiences in cinemas and also from TV and video/DVD, and this fear has been due to various elements. I am susceptible to the quiet, quiet, quiet, BANG! approach to scares, provided sufficient suspense has been built up. Unlike some, I found the remake of A Nightmare on Elm Street quite effective, because it built up the suspense before cutting (literally) to the chase. I find tension and suspense crucial to engaging me in dramatic scenes, be it horror, thriller, action or even melodrama. It sounds trite, but suspense needs to be built up in order for there to be interest in what happens next. I mentioned in a previous post that the criticism “I don’t care about the characters” is not one I tend to use, because what hooks me is the desire to know what the subsequent event will be or how the current event will play out. For this engagement, suspense is essential.

The limitation to the suspense-followed-by-jump approach in horror is that these shocks are very transitory, as the immediate reaction after the jump is often a laugh of relief or a quasi-angry “DON’T do that to me!” The result of this reaction is that the fear is quickly released and is followed by relief. Truly terrifying movies, like those I list here, operate on a far deeper level and the fear remains long after. In a word, the scariest movies, for me, combine suspense, shocks and are disturbing. Psychological horror, what you don’t see is far more frightening that what you do, striking deep chords, all these terms come down to something that is disturbing, and a truly terrifying movie for me is one that stays with me and leaves me feeling uncomfortable for a long time.

To wit, I shall offer my five top films that, in a series of ways, scared the bee-jesus out of me. Some honourable mentions go to those that give me the creeps, but did not quite make the Fearful Five. In no particular order, they are:

Halloween (John Carpenter, 1978)

Having seen parodies and read pieces about Halloween, it is perhaps not surprising that when I saw it the overall scare factor had been diluted. Nonetheless, it is still an affective chiller, mainly by virtue of Carpenter’s maintenance of suspense (there’s that word again), especially as Michael tends to watch his victims before attacking.

The Shining (Stanley Kubrick, 1980)

Another obvious one, and one that did not scare me until I saw it on the big screen at a university showing. The scale, particularly with the sound booming around me, drew me in more than a TV viewing had, and while Jack Nicholson crowing and swinging an axe is certainly aggressive, what troubled me more was the sense of being drawn into a world that is not to be trusted. Perhaps like the character of Jack himself.

Alien (Ridley Scott, 1979)

In space, no one can hear you scream. In the cinema, everyone can. Alien, perhaps ironically, creates a thoroughly creepy atmosphere, with the effect that it’s almost a surprise the Nostromo needed to pick up a monstrous passenger. Shouldn’t it have been there all the time? Thoroughly unsettling.

The Blair Witch Project (Daniel Myrick, Eduardo Sánchez, 1999)

When it first came out, this was a surprise to many people, myself included. Oddly, it isn’t until the final frames that the true fear actually gripped me, but on reflection I realised that it had been creeping up on me the whole time. I’ve only seen this film once, over ten years ago, but I still remember the absolutely chilling final image of one a character standing in the corner, waiting to die. Haunting.

The Ring (Gore Verbinski, 2002)

Yes, I know, sacrilege to rate the remake over the original! I don’t care, Verbinski’s film creeped me out and had me curling into my armchair. The slow-burn approach is very effective as, again, it builds up the suspense and left me waiting for something horrible to happen. And it wasn’t disappointing when it did.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (Tobe Hooper, 1974)

Remarkably bloodless, considering its title, but the sheer random brutality of this film makes it both frightening and bewildering. The moments of Leatherface running around and waving that chainsaw are comparable to a wounded animal, but the worst moment comes earlier, when he grabs one of the girls and carries her into his lair. Her screams are heartrending and make me both want to go and help her, and run away as fast as possible. Empathy can be an effective tool in horror – if someone’s fear is well expressed then it can be shared.

Wolf Creek (Gregg Mclean, 2005)

This Australian shudder-fest is a very recent addition, which I saw for the first time earlier this year. The tale of three young people and the lunatic they meet in the Outback could have been lurid and gruesome, and it is, but it is also disturbing and thoroughly creepy. There are various points when it appears to be following conventions of the slasher genre, but then takes an unexpected turn. Wolf Creek features as menacing a screen psychopath as you are ever likely to have the misfortune of running into, and the merciless sun throws the plight of the young victims into sharp contrast against the baked Australian wilderness. For it to be based on a true story is even more chilling, and I genuinely had trouble sleeping after seeing this one. No road trips across Australia for me!