Home » Posts tagged 'Jessica Chastain'

Tag Archives: Jessica Chastain

95th Academy Awards: Results

If you’re like me, you love watching the Oscars and stayed up until stupid o’clock watching the show. Then again, if you’re like me, you’re an academic- film critic-podcaster with a blog who likes to think he’s funny. What’s that all about?

Anyway, as you may have heard, the 95th Academy Awards took place on 12th March, and there is much to say about the results. The Oscars is the only thing I would place a bet on, but I never do. Had I done so this year, I might have won something because my predictions were largely correct. Look back at my earlier posts and you’ll see I picked the winner in multiple categories including Animated Feature – Guillermo Del Toro’s Pinocchio, Sound – Top Gun: Maverick and Visual Effects – Avatar: The Way of Water. I was incorrect with my picks on Documentary Feature, which went to Navalny; Adapted Screenplay which went to Sarah Polley for Women Talking; Black Panther: Wakanda Forever received Costume Design; and Original Song, which was awarded to ‘Naatu Naatu’ from RRR, a very pleasing win for a film that received no other nominations but was certainly a major talking point last year.

The aforementioned films all received one award apiece, while The Whale won two, repeating the pattern of Darkest Hour and The Iron Lady by winning Makeup and Hairstyling and a leading performance. The now Academy Award winning Brendan Fraser’s speech was one of many that were deeply earnest and heartfelt. Tolerance for such gushing emotion will vary, and personally I love it and wanted to enfold the tearful Fraser in a warm hug. For those of us who have loved Fraser since (or even before) The Mummy, this was a fitting sight for this always engaging and likeable screen presence.

Overall, the evening was largely dominated by two films. After cleaning up nicely at the BAFTAs, All Quiet on the Western Front proved a significant awards magnet for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. As a Best Picture nominee, it was always likely that AQOTWF would collect International Feature, as indeed it did. In addition, Edward Berger’s haunting and harrowing adaptation of Erich Maria Remarque’s novel received awards for Cinematography, Production Design and Original Score, all of which were correctly predicted by yours truly, if you care.

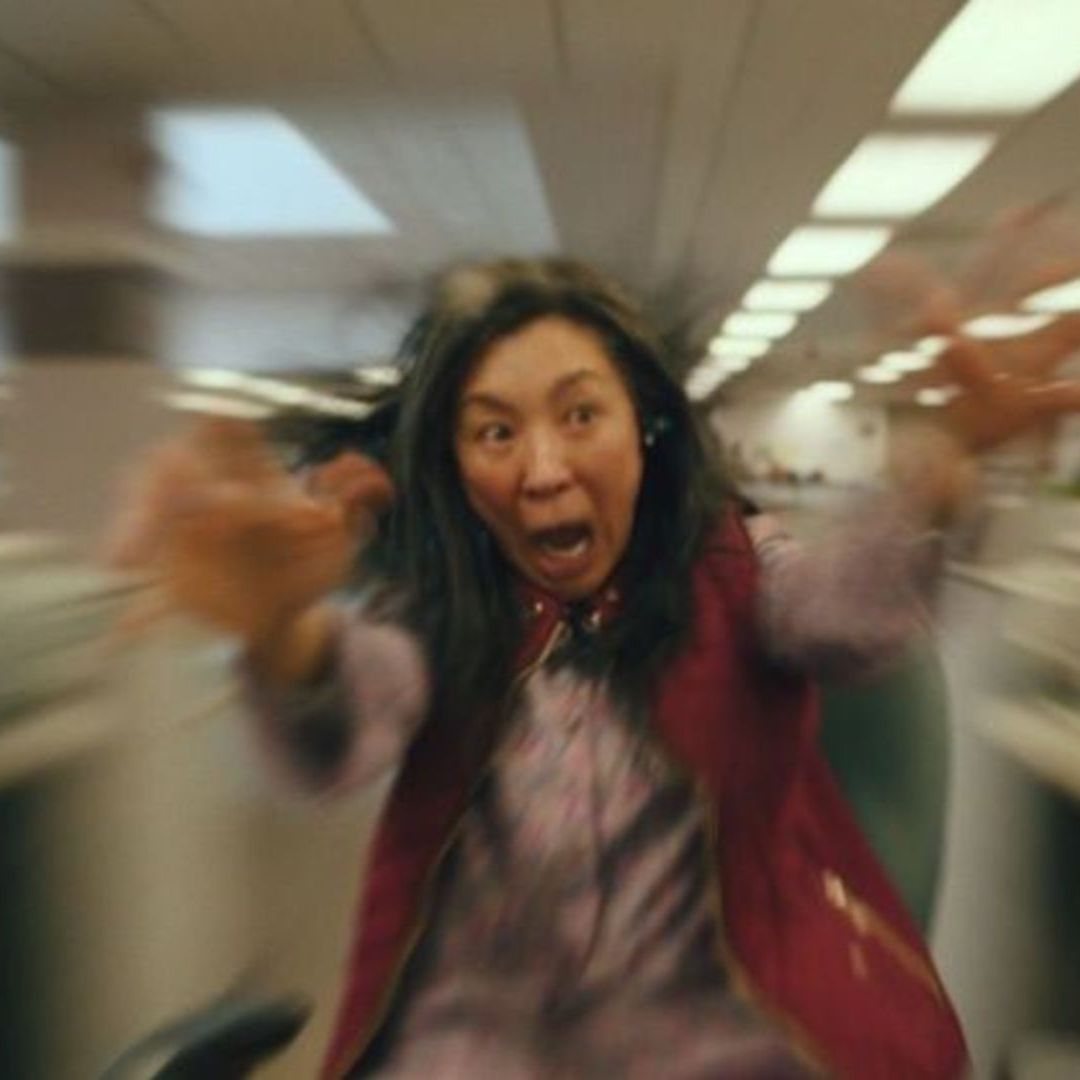

However, the big story of the night was the little film that did. A tale of an immigrant family struggling with laundry, taxes, duty, disappointment, ennui, hot dog fingers, martial arts, combat, fame, identity, googly eyes, puppeteering racoons, bagel black holes and the sheer extraordinariness of the everyday across multiple universes is possibly the most deranged fever dream to ever win Best Picture, and the first science fiction film to receive this award. Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert’s mad work of genius garnered a total of seven Oscars (all of which I predicted correctly), including Directing, Original Screenplay, Editing, Actress in a Leading Role for Michelle Yeoh, Actor in a Supporting Role for Ke Huy Quan and Actress in a Supporting Role for Jamie Lee Curtis. Curtis’ reaction at hearing her name announced as the winner was priceless as you could clearly see her say ‘OH SHUT UP!’

Curtis’ acceptance speeches paid tribute to the horror genre where Curtis made her name, declaring that the fans of her earlier work had all won the Oscar with her. Quan’s speech was highly emotional and paid tribute to his family who entered the USA on an immigrant boat, a sentiment echoed by the Daniels who also indicated their humble beginnings. As the first Asian performer to win this award, Yeoh called out to all the girls who ‘look like her’, and that women are never past their prime. Plus there was something lovely about seeing Yeoh alongside fellow Best Actress winners Halle Berry and Jessica Chastain. Hats off to all of them.

The seven awards make Everything Everywhere All At Once the biggest award winner since Gravity in 2013 (though that did not win Best Picture). The film’s history is the stuff of Hollywood itself – independent filmmakers who previously made a couple of quirky comedies and then put together a bizarre but deeply affecting tale that combines multiple genres, references, styles and concepts and somehow resonated with audiences, critics and the Academy.

It will not surprise me when sniffy attitudes emerge that downplay the success and claim that other films were ‘better’ and should have won, because there are always those who say they know best. I had an issue or two with EEAAO, and perhaps Tár overall impressed me more, but I am delighted that such an out-there film did so well. As I have mentioned previously, in recent years the Academy has demonstrated an openness towards more radical films than it used to, and in an era where cinema is frequently criticised for safe and formulaic material, the success of Everything Everywhere All At Once is something to be applauded.

X-Men: Dark Phoenix

The superhero genre groundwork was laid by the Superman and Batman franchises, improved by Blade, and received its first fully formed incarnation with 2000’s X-Men. The subsequent 19 years delivered a further eleven films, ranging from the highs of X-2 and Logan to the lows of X-Men Origins: Wolverine. X-Men: Dark Phoenix is, sad to say, another low. There are many familiar features, from visual renderings of telepathy to energy blasts from eyes, but there is little that’s new or interesting. Writer-director Steven Kinberg displays little flair or innovation, making the viewer pine for the stylistics of Bryan Singer (controversy notwithstanding) or Matthew Vaughn. Action set pieces on a space shuttle and aboard a train pale in comparison to earlier entries in the franchise as well as those in Marvel Studios’ output. That said, Kinberg does manage to evoke a sense of atmosphere, fitting for the steady and dangerous increase of power in Jean Grey (Sophie Turner). At their heart, superhero films are always about power and its appropriate use, and Dark Phoenix does continue this conceit in relation to Jean, and also Charles Xavier (James McAvoy), but without any significant depth. Indeed, much of the early part of the film is fairly bland, despite potentially shocking moments, though it does pick up slightly when Erik Lensherr/Magneto (Michael Fassbender) appears. Despite the best efforts of the cast, and a prominence of female characters, the strongest element of the film is the score, with Hans Zimmer at his most Hans Zimmer. Crashing synths and booming Braaaaaaahms abound, adding to the atmosphere even if the end result is somewhat hollow. As a chapter in the franchise, Dark Phoenix feels conclusive, and it is a damp squib for this long running series to go out on. But then again, you can never keep a good (or bad) mutant down.

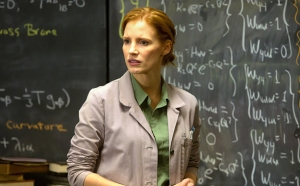

Miss Sloane

American politics. A dramatic landscape where power, corruption, laws, ethics, ambition and manipulation interweave and vie for dominance. In the tradition of Mr Smith Goes To Washington, All The President’s Men and The Ides of March, Miss Sloane focuses on the movers and shakers at the periphery of elected officials, specifically the eponymous Elizabeth Sloane (Jessica Chastain), a lobbyist for a major firm with a ruthless desire to win. Sloane is initially approached by a pro-gun group to aid their cause against firearm restrictions, but after (literally) laughing in their face she goes to work for the supporters of this legislation, an organisation run by Rodolpho Schmidt (Mark Strong). Thus ensues much verbal sparring, scheming and, at times, grandstanding and breaking down. First time screenwriter Jonathan Perera delivers sharp dialogue, a twisty story and some truly amazing sucker punches. John Madden directs with crispness and efficiency, sometimes replaying events to allow the viewer further information that was previously withheld. Wisely, the film is not overloaded with its own politics – corruption is presented as a larger enemy than devotees of the Second Amendment, while the significance of gender is part of the scenery rather than a central focus. Sloane often comes up against entrenched masculinist attitudes but her skill and effectiveness is not specifically tied to her gender. The film offers a powerful brace of performances including those of Mark Strong and Gugu Mthawa-Raw, but make no mistake that this is Chastain’s film. Whether displaying a ‘granite wall’ when facing down a Senate committee, holding team meetings in unforgiving yet jocular fashion, delivering impassioned TV debates on gun control or revealing the vulnerability that lies beneath her seemingly unflappable exterior, Chastain is mesmerising and utterly compelling. There are few performers who can power a film with such relentless pace, but she is certainly one of them.

The Zookeeper’s Wife

Humanity’s inhumanity is a common feature across many cinematic genres, often contrasted with compassion and sympathy. The Zookeeper’s Wife joins the sub-genre of Holocaust dramas, at times feeling like an odd combination of Schindler’s List and the first act of Life of Pi. Antonina Zabinska (Jessica Chastain) is the eponymous spouse of Dr Jan Zabinski (Johan Heldenbergh), curators of the Warsaw Zoo before and during the Nazi occupation of Poland, who hide Jews in the zoo’s facilities. The early scenes of the film are the most effective, as director Niki Caro presents the zoo as an idyllic setting and Antonina as an ideal maternal figure both to humans and animals. A bombing sequence is presented from the perspective of the zoo animals: tigers, camels and zebras (among others) panicking and escaping, before being shot by soldiers in genuinely distressing moments. Unfortunately, the film fails to draw effective parallels between cruelty to humans and animals, perhaps limited by the true events upon which the source novel by Diane Ackerman is based. The subsequent concealment of Jews and the network of resistance allows for some tense moments, but antagonist Lutz Heck (Daniel Brühl) is too peripheral to be more than occasionally menacing. The final act of the film also drags and, while there are moving moments such as Antonina comforting a victimised girl with a rabbit, the end result is uneven. The story is remarkable and much of the film is handsomely mounted, but Caro’s handling of it is ultimately unsatisfying.

The Huntsman: Winter’s War

Recent film adaptations of fairytales are a mixed bag. For every Frozen there is a Hansel and Gretel: Witch Hunters. Snow White and the Huntsman was a decent expansion of the Snow White story, turning the ‘fairest of them all’ into a Joan of Arc-esque warrior. The Huntsman: Winter’s War is both a prequel and sequel, explaining how Eric the Huntsman (Chris Hemsworth) came to where we first see him in the earlier film. The backstory also raises points that are then developed following the events of Snow White and the Hunstman. And that’s about it. While the fantasy world is prettily designed and there are some interesting formulations of the magic of sister sorceresses Ravenna (Charlize Theron) and Freya (Emily Blunt), director Cedric Nicolas-Troyan fails to give the film an epic sweep or battle scenes that are more than functional. On the smaller scale, Eric and Sara (Jessica Chastain) are passably engaging as romantic swashbuckling heroes (despite distracting faux-Scottish accents), but their story similarly lacks heft and impetus. The film swings unevenly between romance, action and comedy, the last of which is largely provided by dwarves Nion (Nick Frost), Gryff (Rob Brydon), Mrs Bronwen (Sheridan Smith) and Doreena (Alexandra Roach). This unevenness is the main problem – the film never seems sure of its agenda and, as a result, the handsome production design and sometimes stirring music has little dramatic meat to add to. The Huntsman: Winter’s War is passably pretty, but ultimately (and not in a good way) leaves the viewer just a little cold.

Crimson Peak

“Ghosts are real” insists heroine Edith Cushing (Mia Wasikowska) in the opening voiceover of Guillermo Del Toro’s spine-tingling Crimson Peak. The viewer of this simmering gothic romance has little trouble believing Edith’s assertion, as ghosts appear in such crawlingly tactile form that you may check there are no cold fingers touching you. Nor are these apparitions out of place, as Kate Hawley’s sumptuous costumes and Thomas E. Sanders’ lustrous production design immediately draw the viewer into an evocative supernatural world. Playing as an unabashed haunted house story, Crimson Peak unfolds with confidence and cunning, as Edith finds life with her new husband Sir Thomas Steele (Tom Hiddleston) and his sister Lucille (Jessica Chastain) to be far from comforting. Del Toro rewards expectations by playing to the genre, utilizing his love for ghosts and monsters and sharing these with the viewer. Along the way there are moments of brutal violence and sinister motives, as well as tensions around modernity and tradition, gender, nationality and class. The result is a heady and potent mix, lovingly rendered and gorgeously presented in another triumph for this distinctive auteur.

The Martian

Ridley Scott’s adaptation of Andy Weir’s novel The Martian is one of the director’s most accomplished films in a long time. The film’s success is partly due to Scott’s stunning visual style, rendered in gorgeous visuals by DOP Dariusz Wolski, where vast desert landscapes express the terrible isolation of Mars, in sharp contrast to the supportive, enclosing environments of Earth. Credit must also be given to Drew Goddard’s witty and engaging script, Matt Damon’s roguishly charming performance as Mark Watney and Pietro Scalia’s smooth editing, all of which combine to keep the film flowing easily but informatively. Due to an accident during an evacuation, Watney is marooned on Mars and must ensure his own survival or, as he puts it, “science the shit out of this.” What follows is a hugely engaging portrayal of ingenuity and determination, as Watney uses his own waste to fertilise a potato patch, creates water from the requisite ingredients, and records multiple video diary entries as a record of his experience. Meanwhile, his NASA colleagues both on Earth and aboard the spaceship Hermes grapple with the personal guilt of leaving Watney behind and the practical difficulties of helping him stay alive. This singular goal permeates the entire film, and allows for fine humour as Watney comments on his surroundings, political tensions as NASA director Teddy Sanders (Jeff Daniels) clashes with department heads Vincent Kapoor (Chiwetel Ejiofor), Mitch Henderson (Sean Bean) and Annie Montrose (Kristen Wiig), scientific and engineering problems on both Earth and Mars, and some nail-biting set pieces where physics is an inexorable antagonist but also the only means of survival. Despite these apparently disparate elements, The Martian is a bravura success, a gripping and perfectly-paced survival story filled with wit, brio and invention.

To Infinity, and Beyond: Sci-Fi Countdown – Introduction

As a completely unofficial tie-in with the British Film Institute’s science fiction season, Days of Fear and Wonder, I’ve prepared a countdown of my top five science fiction films that transport the viewer to fantastical environments. At its best, science fiction can be the ultimate cinema experience, as it creates another world and takes you to distant places and times. These are not necessarily the greatest science fiction films of all time, but they are all films that take the viewer on a remarkable journey. The next few days will feature a countdown of my top five transportive science fiction films, beginning with…

As a completely unofficial tie-in with the British Film Institute’s science fiction season, Days of Fear and Wonder, I’ve prepared a countdown of my top five science fiction films that transport the viewer to fantastical environments. At its best, science fiction can be the ultimate cinema experience, as it creates another world and takes you to distant places and times. These are not necessarily the greatest science fiction films of all time, but they are all films that take the viewer on a remarkable journey. The next few days will feature a countdown of my top five transportive science fiction films, beginning with…

Honourable Mentions

Star Wars (1977)

The cultural impact of Star Wars can never be over-estimated, and for its time it was an extraordinary piece of groundbreaking cinema. While I do not find it particularly transportive and its script and direction is ropey in many places, it remains an undiluted thrill ride through a far away galaxy, a long time ago.  Contact (1997)

Contact (1997)

Contact’s journey is as much about travelling into the heart and mind as it is about a journey to a distant world. An intelligent science fiction film that explores humanity on Earth while also reaching out to the stars.  Solaris (2002)

Solaris (2002)

Steven Soderbergh is a great utiliser of editing and cinematography, which sometimes collapses into irritating style for its own sake. In the case of Solaris, however, the discontinuous editing takes the viewer both into a grieving mind and to a strange world where time, memory and reality blur together and nothing is what it seems.  WALL-E (2008)

WALL-E (2008)

One of Pixar’s finest films conveys both the ghastly isolation of an abandoned Earth and the expansive wonder of space. One is gloomily familiar and the other a source of inspiration and beauty, best demonstrated in the space dance sequence between WALL-E and EVE. But perhaps most importantly in WALL-E, the journey to the final frontier is not only transportive but transformative, as humanity, led and inspired by little robots, returns to the Earth that is our home.  Interstellar (2014)

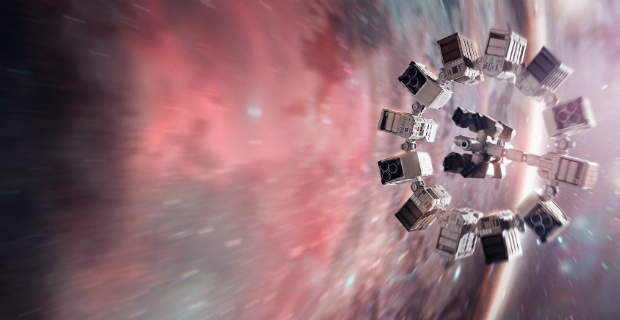

Interstellar (2014)

The most recent entry and a convenient release for the BFI’s season (Coincidence? Unlikely). Fear and wonder populate Christopher Nolan’s sci-fi epic: fears include the horror of ecological devastation as well as the vacuum of space, balanced with the spectacle of Saturn as well as spherical worm holes and alien landscapes. Interstellar echoes earlier films such as 2001: A Space Odyssey, Silent Running and Contact and, while it sometimes tries too hard to explain everything, it remains a breathtaking journey into the infinite.